Matthew Thorburn, Poet - Author of Dear Almost

Menu

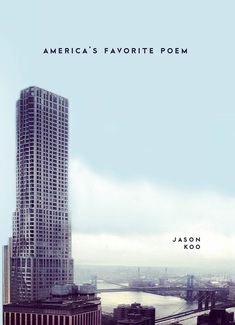

Jason Koo is the author of two collections of poetry, America’s Favorite Poem (C&R Press, 2014) and Man on Extremely Small Island (C&R Press, 2009), winner of the De Novo Poetry Prize and the Asian American Writers' Workshop Members' Choice Award for the best Asian American book of 2009. He has published his poetry and prose in numerous journals, including the Yale Review, North American Review and Missouri Review, and won fellowships for his work from the National Endowment for the Arts, Vermont Studio Center and New York State Writers Institute. An assistant professor of English at Quinnipiac University, he is also the founder and executive director of Brooklyn Poets, a nonprofit organization celebrating and cultivating the poets, poetry and literary heritage of Brooklyn, where he lives. Matthew Thorburn: As Walt Whitman would say, your poems contain multitudes—including the famous and the infamous, from Marky Mark and LeBron James to Tony Leung and Wong Kar Wai, to Tommy Flanagan and Oscar Peterson, to Kim Jong Il and, appropriately enough, two poets associated with Brooklyn, Hart Crane and Whitman himself. Your cat Django even makes an appearance or two. I’m not someone who says certain subjects or people are or aren’t appropriate for poems, but this cast of characters definitely includes some surprises. Is this something you’re conscious of? Do you try to expand the frame in your poems to include less obviously “poetic” individuals or subjects? Is there anyone you think couldn’t appear in a poem? Jason Koo: Yes, I’m definitely conscious of this, but less so than I used to be. I remember when I was starting out and fearing the wrath of T. S. Eliot if I included any mention of pop culture in my poems. The liberation came, of course, when I started reading the New York School poets and seeing how they swerved past all the Eliotic rules, not just writing about figures from pop culture but each other and their friends. They made everyone “famous.” And probably more than any other “school” of poetry they expanded our sense of what poetry could do—what poetry could be. I’m always in favor of a poetry that is more and more inclusive of what’s out there—especially things like sports, which are strangely left out of most contemporary poems. We live in the age of pop culture–infused poetry, so it’s no surprise, I think, to see movie stars and musicians and superheroes appear in poems, but very rarely do you see contemporary poets mention sports—probably because so few of them watch sports. I’d say this is unhealthy, but of course watching sports is far unhealthier. Not sure if there’s anyone I think who couldn’t appear in a poem—if I ever thought this I’d probably immediately want to try to write a poem with that person in it. Like once I was told by a famous poet in a one-day workshop that I could never use the word “phone” in a poem (I had that word in the poem being workshopped), and my attitude was like, Now I’m going to use that shit all the time. Come to think of it, though, I’m not sure how often I’ve used the word “phone” after that.  MT: Recently I’ve been thinking through the structure and sequence for a new manuscript, so I’m especially curious to hear how you put this book together. It seems like each of us figures out how to do this in a different way—and I’ve found (so far, at least) that it’s different each time, based on each manuscript’s particular set of poems. Could you talk about how you approached this with America’s Favorite Poem? Did you have an idea of how this book would come together as you were writing, or did that come later? And was it different from your experience with your first book, Man on Extremely Small Island? JK: The structure of both books came together as I wrote the poems and started putting them together. It would be very odd, I think, to think of a structure first and then write the poems. Well, maybe not odd, but almost certainly leading to crappy poems. With Man, I always had long poems in sections II and IV, though those ended up changing, which made me want to balance them with collections of “shorter” (that’s in quotes because you know my poems are almost never short) poems in sections I and III. In the first versions of Man, sections I and II were fairly affirmative and inclusive about the world—a lot of the poems came from my time in grad school at Houston, when I was so excited about possibilities. The long poem in Section II was called “Open Sky,” a poem about driving under the huge skies in Houston listening to jazz. But then I moved to Missouri for my PhD and started writing a lot of poems about loneliness and alienation, and these changed the tenor of the book. I thought of Section III as the darkest, loneliest section, so I tried to put all these poems in there, but my friends kept telling me to put them up front, because they were stronger than the poems there. Eventually I relented when I wrote “2046 Love Songs of Wong Wai,” because I thought that was the best thing I’d written and wanted it in the book somewhere. I replaced “Open Sky” with that poem and then the whole first section suddenly seemed unrelated. So I very quickly wrote a bunch of sad, lonely poems that went into the first section—this is making my process sound ridiculous, I realize—and then the book, I felt finally, was very coherent. That was the summer before it won C&R Press’s first book prize in the fall. I should add that I also wrote the last long poem of the book about my dad in Missouri, which replaced an even longer letter poem I’d written to James Schuyler—I loved that poem but it was 17 pages in ms. and created a huge imbalance in the book. So you might say the history of assembling my first book was a history of me taking out my loves and affirmations and replacing them with more loneliness and despair. Good times. For America’s Favorite Poem, I knew I didn’t want to write any long poems on par with “2046 Love Songs” and “Bon Chul Koo and the Hall of Fame.” I was conscious of wanting to write “shorter” poems—or at least build the book differently. I didn’t want a four-part structure with two long poems in sections II and IV again. That was pretty much all that went into my opening thinking about the structure of the book. But of course then you have to write the poems. And I didn’t really write many “shorter” poems—even the two sonnets in the book actually came from a summer workshop I’d taken with Henri Cole before my first book came out. I saw that I was writing a lot of longish but not “long” poems—at least not how I’d define a long poem. Poems like “Giant Steps” and “Model Minority” and “Sometime Sweep” and “Struck from the Float” and “Work” that were 3-5 pages in manuscript. One nice thing about writing longish (and long) poems is that pretty soon you have enough material to put together a book. So within about a year and a half of my first book coming out, I had something like a first draft of America’s Favorite Poem—that would’ve been the end of summer in 2011. I sent it to my readers and revised poems and shifted poems around and eventually added a poem or two—I think “Lunch Special” was the last one to go in there. I did end up writing one long poem, “Close Embrace,” that I was worried I’d have to put into its own section, but I liked how it worked in the middle of Section II so I left it there. I again went with a proem to the collection, like I did in Man with the Effingham poem, and this time added a coda poem: “Work.” The first section of the book includes what you might call poems of ego, poems in which I’m both reveling in and detesting big projections of the self—maybe we should call this the Yeezy self. Boy am I sounding ridiculous now (which is incidentally a good description of the first section). The second section is more introspective, a little lonelier—more like the poems in Man. In these poems I’m investigating the fallout of all those projections of the self on my personal relationships. Okay, I think I’ve done enough harm to myself with all these descriptions of what I’m doing as a poet, so I’ll stop. MT: This book opens with “American Dream,” a villanelle in dialogue with one of Shakespeare’s sonnets, and ends with “Work,” a more sprawling (formally and narratively speaking) poem that brings together different ideas about work, from Django the cat’s work (sleeping, mainly) to your work as a professor, to Andy Warhol and his Factory, to your father working to send you to school, and finally (as I read it) to the finished “work” that is this poem and ultimately this book. These seem like fitting bookends to a collection that is wide-ranging in terms of formal approaches (that villanelle, an erasure poem, a variety of stanza forms) and full of language that thinks about and is sometimes self-conscious about language, yet also often very personal and intimate. Would you talk a little about how these different strands come together in your work? JK: First of all, that is a damn good reading of the book! Affirms my faith in the reader actually noticing what I am trying to do. I was happy with the formal variety of the book, something I’m always going after, though I think there’s a little more of that in America’s Favorite Poem than Man on Extremely Small Island. For me, American poetry has always been and always will be about inclusiveness, and that should start with a poet’s approach to form. We’re the inheritors of two great formal traditions seemingly opposed to each other in Whitman’s long free-verse lines and Dickinson’s incredibly compressed ballad meter. I love both poets. And what’s great about American poetry, as my old teacher Sandy McClatchy used to say, is that it operates between these two frequencies. I think it’s because of Whitman and Dickinson in the 19th century that American poetry flourished in the 20th century: there was so much room for poets to innovate formally between those two frequencies. One of the reasons I love Hart Crane (aside from his growing up in Cleveland) is that he was the first American poet who seemed to try to fuse Whitman and Dickinson together, to have both expansiveness and intensity in his lines. I think this is why he loved the Brooklyn Bridge so much, because it seemed to wed expansiveness and intensity. I too am always trying to have it both ways: a poetry that can be expansive as well as intense. I love writing long, overlapping lines a la Whitman but also blank verse, villanelles, sestinas, poems in syllabics, and other more contemporary forms (or perhaps anti-forms) such as erasures and found poems (the GQ poem is basically a found poem) and mashups (the Van Gogh poem). The whole point of America, or what should be the whole point, is that it is inclusive, that we are free and open to everything—and as a poet I want to reflect this and celebrate it. To that end I’m a little mystified by American poets who feel they have to pick between free verse and “traditional” verse or never try anything new formally.  MT: How does a poem start for you? Specifically, could you talk about “Self-Installation” and “What We Talk About When We Talk About”? How did each of these poems start, and what was the writing and revising process like? JK: Like a lot of poets, usually a poem starts for me with a phrase or line I have in my head. There’s something that catches in the auditory imagination—you feel there’s more there for you to explore in the phrase or line, a whole world for you to open up. And actually both of the poems you mention started this way: “Self-Installation” began with a sentence straight out of Van Gogh’s letters—“It seemed less and less like eating strawberries in spring”—and “What We Talk About” began with a funny message I’d received on Facebook from my girlfriend at the time—“I thought I should write this down, since your ear / is a vagina and you might not hear it if I said it out loud.” Obviously when you hear those two sentences side by side you can hear two different worlds possible in each of them, two different tonal avenues. The Van Gogh sentence seemed destined to lead to a devastating love poem, what I think of as Ben Webster mode, and the line about the ear/vagina seemed to be leading to a wacky, laugh-out-loud kind of poem. In some ways I think of myself as operating between those two tonal extremes, sometimes within the same poem. It’s interesting that you picked these two poems, and that they appear back-to-back in America’s Favorite Poem. The writing process for each of them differed a bit in that the Van Gogh poem used a lot of other phrases and sentences from Van Gogh’s letters in addition to the first one; I started riffing off repetitions of less/more and returning to Van Gogh’s words to push my own words further. I’d never actually written a poem that way before; more riffing/associative than narrative/dramatic, as most of the work in my first book is. More disjunctive and language-centric. I remember debuting this poem at a reading at Lewis University, where my friend Simone Muench had invited me to read, and her ecstatic response to it, I think because stylistically it was closer to her style and she could feel the breakthrough from my usual style. “What We Talk About” is more like my other poems, mixing funny and weird and sad and essentially telling a little story; I wrote this at the Vermont Studio Center in January of 2010, the month after my first book came out. I believe it was the second poem I wrote. Hence the similarity in style, tone and subject matter to the poems of my first book. I can’t remember much about the revision process; I think it came out mostly all at once, but I do remember having a little trouble with the ending. The original ending I believe went a little further than just “You’re covering your vaginas”; then I realized that I couldn’t really go past that line. I mean, how do you go past “You’re covering your vaginas”? That’s tough. I also remember having a little trouble with the title, eventually settling on what I thought might be a too cute play on the famous Raymond Carver story title “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.” Obviously the idea here was that “love” was not talked about in my poem; and I liked the play on “about,” how there was a talking “about” going on in the sense of talking around or all over the place, i.e. “walk about.” The Van Gogh poem came out very quickly and went through only minimal revision, mostly just cutting/changing a few words. And I think for that poem too I changed the title; I think the original title was “The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh,” but that didn’t seem to do enough work so I did another possibly too-cute title thing with “Self-Installation.” I have a series of possibly too-cute titles for poems that are essentially self-portraits but which I see as not being traditional in the sense of something painted: “Self-Reproduction with Scream Pillow,” “Self-Montage with Noodles,” “Self-Installation.” I saw the self in “Self-Installation” as just an empty room with things in it, kind of like many installations (yawn), rather than like one of the electric self-portraits in oil paint that Van Gogh used to make. MT: It’s kind of sad to say, but you are one of the relatively few poets I know who published both his first and second books with the same press. What has your experience been like working with C&R Press? What advice would you give to someone seeking out a publisher for a poetry book manuscript? JK: My experience has been good and bad, as probably most poets’ experiences with presses have been, whether that press is a major house or university press or an indie press. The problem, of course, is that poetry doesn’t really sell, so most presses don’t allocate a lot of resources to it. The presses I think that are good, i.e. with taste in what they publish and strong design and editing and savvy promotion of their catalog, usually have a boatload of funding they can throw at their poetry titles, whether that be from private resources or nonprofit grants and contributions. C&R has been good to me in that they allow me a lot of flexibility in choosing my own designer to design my book covers and let me be as OCD as I want when it comes to that design and the editing of my text; the downside is that they don’t do a lot of promotion of my books and rely on a business model whereby I, the author, do a lot of the buying (40% off) and selling of my own book, as well as the promotion via readings and social media, etc. They like me because I’m good at those things and have a ridiculous amount of energy. In many ways the second book felt more like a partnership than the first book. I’d shopped the book to a few of those aforementioned “good” presses that I thought have more reach than C&R and entered it in some contests, and it got close but wasn’t taken; and I didn’t want to wait more than a year to land a book contract because of the pressures of the job market, my thinking being that entering the job market with two books to my name would be stronger than just having one. C&R kept asking for the manuscript so eventually I gave it to them and we worked out a deal that was beneficial to both parties. Knowing what I know now about the business side of the poetry world and how to promote work and set up events, I might be better off just publishing my own books and selling them on my own—in the sense that I’d probably make more money. But from a credentials standpoint obviously that wouldn’t be the case, as all academic jobs frown upon self-publication. You need the cultural imprint of a press to make your work legitimate, but what’s funny is most academics who aren’t poets don’t know the difference between C&R Press and Wave Books and Copper Canyon. If it ain’t Knopf or Penguin or Norton, etc, it’s all the same to most academics. My advice to someone seeking out a publisher is to make sure you like what that press is doing. You should like what they’re doing from all angles: the kinds of books they publish, the design, the promo. That said, there aren’t many presses that will do all of those things well, and the reality is that as a poet you don’t have a lot of time to wait while you’re trying to land a teaching job (if that’s the line of work you’re in). So you’re probably going to have to compromise a bit. And that would be my second piece of advice: be prepared to compromise, but do so in a way that you feel still maintains your artistic integrity. I think we all have a little wiggle room with our integrity, but there’s a line we feel we can’t cross without feeling eternally shitty about ourselves. So if I was ever with a press where they wanted to publish some horrible cover for my book that I absolutely hated, or if they wanted to edit my lines in a way that felt like a violation, I would probably withdraw the book. I think if you ever get to a place in your career where you can afford to wait for a press to publish your book that you really like, you should do that. I think also as you get older you start to have a better idea of what presses would be good for your work at that particular stage of your career—and you start to cut out other presses that you know would not serve you anymore. You might even meet some of the publishers/editors of those presses and have more of an “in.” For the new manuscript I’m working on, I have an idea of the presses I’d like to publish it who might be interested in it; but we’ll have to see how things work out. In my experience, poetry publishing does not generally work out the way I want it to. MT: In addition to writing and teaching, you are also the founder and executive director of Brooklyn Poets, a nonprofit organization that celebrates and cultivates poets and poetry in Brooklyn. That seems like a full-time job in itself, so I’m curious to hear how you balance these different roles—and find time for all three. And does your work with Brooklyn Poets influence your own writing? What are you working on now? What’s next for you? JK: Directing Brooklyn Poets is indeed a full-time job. Sometimes I wonder myself how I balance all three roles of directing BKP, teaching full-time at Quinnipiac and writing. Somehow, some way, the work gets done. It helps that the “full-time” job at Quinnipiac entails teaching two or three times a week, depending on the semester, and that I have fully paid summers and winter vacations, etc. I write mostly in the summer months and winter break. I’ve found as I get older that I can write a lot of poems during my breaks—this summer I wrote essentially a whole new book, longer in manuscript form than either of my first two books. I wasn’t expecting to do that but wham, it happened. Probably that torrent had something to do with the fact that the two years before that I barely wrote any poems. Those were the years in which I founded and developed Brooklyn Poets; I could “excuse” myself from writing new poems without feeling too guilty about it because America’s Favorite Poem was in line for publication and individual poems from it were appearing in journals during that time. And I was also writing and publishing prose. So it’s not like I wasn’t working. I have a pretty good sense of my process now and don’t have much anxiety about not writing new poems; I know any down time is good time, because I’m storing up material and building up an internal pressure that will eventually release itself into poems. But doing the Indiegogo campaign last fall for The Bridge was very difficult; that was one time in my life where I reached a point that I wasn’t sure if I could balance all three roles. I found myself nodding off a couple of times during workshops last fall—crazy. Absolutely offensive; I remember how furious I was in grad school when I noticed one of my older professors falling asleep during someone’s presentation. I was getting about three hours of sleep a night during November (the last month of the campaign), but that was no excuse. You’ve got to be there for your students. But I got through the campaign, we funded the development of The Bridge, and now, a year later, things are much better, more balanced. Brooklyn Poets is to the point where I’ve got a handle on how all our programs run; we’ve got routines, templates (even literal templates for things like our newsletters and posters). The next big thing will be The Bridge, which is in its final development stages; once that launches, my life might change for good, and I’ll have to see how I can manage the new role of managing what’s essentially a social network for poets. But honestly, this kind of work-juggling is what I love to do; I love work. I love my work. The different roles I play now all fulfill a different kind of work that I love to do, whether it’s the private, deeply interior work of writing a poem or the social work of putting on a poetry event. I’m both an extrovert and an introvert. As for what I’m working on now—this interview. Aside from that, as I’ve said: The Bridge; this new manuscript of poems, which includes one mammoth 39-page poem; essays about Asian American masculinity, mostly in embryo (i.e. not on the page). Not sure how much influence my work with Brooklyn Poets has had on my writing, but I am writing more about Brooklyn and my life here than I was my first two years. I think it takes a good 3-4 years in a place for it to sink into your bloodstream to the extent that you feel comfortable writing about it as home. MT: And lastly: what are you reading—or what have you read recently—that moved you? JK: Like a lot of people I’ve been reading Karl Knausgaard’s My Struggle. This summer I finished volume two, so I’m one volume behind a lot of other people I know, including my former landlord, who’s Norwegian. This book had a big influence on the new manuscript I put together this past summer, specifically on that 39-page poem. For better or for worse, we shall see. During the summer I also read through the entirety of Jack Gilbert’s Collected Poems, so I could get a sense of the whole span of his career. Amazing experience reading through all of Gilbert, how steady and monumental his gaze. Great to read Gilbert, too, in the summer light; in July I moved to Williamsburg, and my new apartment has a private roof deck, so all July and August I was up there in the blazing summer light with my shirt off reading Gilbert. Like my own private Greece. Something I just read recently was Frank Guan’s essay “Green House: A Brief History of ‘American Poetry’” that leads off the first issue of Prelude, a new journal he co-edits; that’s an electrifying piece of criticism, maybe the best essay on poetry I’ve read in the last decade. Or, well, decade? I can’t even remember the last time I read poetry criticism I liked. Some books of poetry I loved recently: Cynthia Cruz’s Wunderkammer; Jericho Brown’s The New Testament; Adrian Matejka’s The Big Smoke; Sampson Starkweather’s The Flowers of Rad (which I just got)…and others I’m forgetting. And something that made me cry in my car just a couple of days ago, my best friend Gunny’s email about taking care of his dying father, a great man. I shouldn’t have been reading this in my car, but there I was with one hand on the wheel and the other scrolling through the email on my phone, reading these huge words.

1 Comment

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed