Matthew Thorburn, Poet - Author of Dear Almost

Menu

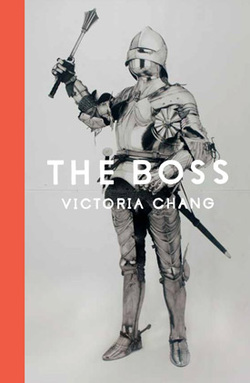

Victoria Chang’s third book of poems, The Boss, was published by McSweeney’s in 2013 as part of the McSweeney’s Poetry Series. Her second book, Salvinia Molesta, was published by the University of Georgia Press as part of the VQR Poetry Series in 2008. Her first book, Circle, won the Crab Orchard Review Open Competition Award and was published by Southern Illinois University Press in 2005. She also edited an anthology, Asian American Poetry: The Next Generation, published by the University of Illinois Press in 2004. Her poems have appeared in Kenyon Review, American Poetry Review, POETRY, Believer, New England Review, VQR, The Nation, New Republic, The Washington Post, Best American Poetry, and elsewhere. She lives in Southern California with her family and her weiner dog, Mustard, and works in business. These poems are written in a very particular and consistent voice and style that, along with the stanza form you use throughout, really tie the collection together as a larger, cohesive whole. What we hear is an anxious, weary voice delivering what feels like a stream of consciousness (especially give there’s no punctuation) interior monologue. Could you talk about how you came to this voice and style, how it developed? “Anxious and weary,” I like that—that pretty much describes my inner state of existence! I felt trapped in my life at the time, having a bad boss, having little tiny kids, and going through an experience where my dad was having major health problems with strokes and aphasia and generally feeling lost, weary, yet urgent. All these things collided and I just started writing these long-lined, stream of consciousness words that were propelled by language—in a way that mimicked my own feeling of loss of control. As I read your book, I found myself thinking of these not only as individual poems, but also as stanzas in a larger poem which is The Boss. Of course you could say this is true of any book of poems—or it should be. But I’m curious if you felt this way when you were writing and revising the poems—if you saw these poems as parts of a larger whole from the beginning, or at what point you realized you were working on a sequence that would become a book—and if that sense had an impact on how you worked on the individual poems. Absolutely. I was writing towards a series; it was clear right from the start that I was writing more than one of these and they built up slowly, one after the other. Each weekend I wrote them in a Honda Odyssey minivan sitting in front of the same tree waiting for my older daughter to finish a language class. It was the quintessential paradox—a “soccer mom” writing poems in a minivan in Irvine. How surreal. I think I got up to 15-20 of these and started feeling tapped out. I was looking for different entry points into this subject matter and noticed Edward Hopper paintings often took place in office spaces, often enough for me to riff off them. I ran out of those too, so I started riffing off of the same paintings but looking at them differently—those were the most fun to write.  Those Edward Hopper poems are another element that unites the collection. What draws you to his work—and how do you feel his paintings connect to what you do as a poet? I love Hopper paintings—I’m not a sophisticated art connoisseur at all but I visit museums and look at art and sculpture often. I am an uneducated art appreciator. I do love Hopper, perhaps as someone might love Billy Collins. I’m drawn to the mystery of Hopper paintings—the mood, tone. They all seem depressed and the characters in those paintings seem so real to me, caught in a moment by an artist. I love them. How does a poem start for you? In particular, how did “The boss tells me” or “Edward Hopper’s Automat” start? And what was your writing and revising process like with these poems? Was it different from writing the poems in your previous books? “The Boss Tells Me” was based on my experiences working with a really wealthy woman, so wealthy it was almost a surreal experience talking to her about her chefs, her assistants, her life, and her billions. Then she went on to marry another billionaire and the experience became more surreal. She was particularly difficult to work with and it got me thinking about how some people like this get so used to having money and power that everyone around them must be subservient at all times. I was forced to work with this difficult woman because I served her well. It was an interesting trap; I served her so well that she only wanted to work with me! It was like being in jail. If I worked poorly for her, she could get me fired. If I defied her or disagreed with her, she could get me fired. If I spoke up, she could get me fired. But if I didn’t work with her and do a good job, my own boss could fire me. It was a constant washing machine of torture and I felt deathly trapped for years. Until I realized that I control myself and that perhaps culturally, I had learned how to be so subservient due to my family and my culture and I could break that cycle myself. This poem started to grow into my other observations about business people and how they turn a blind eye if others are getting treated unfairly to protect their own jobs or reputations and the woman in the office down the hall came into the poem, as did my own complicit self that ignored another woman who had reached out to me a decade earlier because she was being harassed by my boss. As long as I was doing well, I saw no reason to help this woman. It came full circle, and in many ways I felt like I deserved what I got in the end. Working in business, I tell you, is no walk in the park. It’s like a battlefield out there and you have to fend for yourself. I had to learn all of this on my own, of course, having been raised by parents who neither worked in business, nor were from this country. I’m a tougher cookie as a result, but sometimes I wonder if it would have been easier to be, say, a barista! So much of my 20s and 30s was learning how to be American—my parents brought me up to live in Taiwan. I had no compass and no mentors. I had to learn everything through trial and lots of error. “Edward Hopper’s Automat” started as a riff off the painting where this woman was sitting in an automat (not an office painting, but I was drawn to this painting). The woman in the painting looked Asian to me and the tsunami in Japan had just happened and, for whatever reason, I started writing about the tsunami in the context of this painting. And how in such a terrible situation as a tsunami, one doesn’t really care about one’s boss, couldn’t possibly care about the boss, and how I myself needed to remind myself of the bigger picture so that I could survive whatever trauma that I was going through. The writing process for this whole book was magically different than previous books and because I loved it so much, I find myself unable to write again. I am truly blocked. I want to write like this again but I can’t seem to. I haven’t written in 2+ years and finally sat down recently to write something and the stuff is just a bunch of experimentation and I like it for just that. I am not interested in submitting poems to journals either. I’m not interested in the world of publishing, the people in it, the angling, the climbing, none of it. I am just interested in being a bystander and I am truly loving every minute of being a bystander. I, for once in my life, feel free of the literary world. I truly, truly don’t care. It’s magical. I hope it lasts forever. In addition to being a poet, you’re also a mother and someone who, as your bio says, “works in business.” As a new parent myself, I’m curious to know how you balance those three roles and manage to play all three. And as someone who also works in the business world, I have to ask: do you teach or have any interest in teaching? Sometimes I think that I don’t do anything as well as I think I could if I focused more on one of these things or two of these things. However, other times I wonder if this is the way I am made—without all these things pressing against each other, would I have nothing to say? I often look at poets like Matthea Harvey and think that if I had more time I might write more in other genres, write more work (never as good as hers, of course!), but then I realize she is who she is and I am who I am and the results show who I am. I do what I do because I must like doing what I do. I never chose a life like hers. I must have wanted children, must have wanted to work in business (I love thinking about business), must have wanted to write poetry as a secondary project in my life. Otherwise I would have done things much differently. You can’t envy another person’s life if you didn’t choose it. In terms of balance, I just don’t write. And before The Boss, I didn’t write much either. I do like to read, though, but even my reading competes with poetry—I am voracious and read everything. Poetry is only maybe 10-15% of my reading. I’m just the kind of person who is interested a little in everything. Every day is hard, like today I had so many things to do—a dentist appointment (got my tooth pulled), a kindergarten orientation (of which I missed the memo to bring my kid), a conference call with a foundation CEO on China and energy, work in general, board work related to Kore Press, etc.—that I forgot to pick up a kid in the afternoon! The school had to call me to remind me because I had gotten the time wrong. So yes, every day is a challenge. But I choose to embrace my life for what it is because when it is gone, I will miss it. Yes, I love teaching but no one has offered me a tenured-track position job. I am not famous enough or well-regarded enough to have people knocking at my door and I refuse to apply for jobs. If someone offered me a teaching gig, tenure track, I would consider it. But seriously, I like my work too much. Maybe later, Victoria Chang 2.0. I think I would have to be a better poet first, more respected in the community, get more awards, etc. I just don’t know if I have it all in me. I question my talent, I really do. It is definitely not limitless and I’m not sure it’s that great or worthy. Plus I refuse to move. I love California too much. What’s next for you, writing-wise? It seems like I’ve read quite a few of your prose poems in journals over the past few years—are you working on a collection of them? Or something else? Who knows? Maybe nothing. I’m off the rat race of the literary world treadmill, although now I realize I was never really in it. I just wanted to get in that spinning hamster wheel. That makes me happy. I have no ambitious and that is so freeing. Those prose poems were little experiments and I had written two manuscripts before The Boss and sent them out a few times and they were finalists in the NPS and a few other places and then I just stopped sending them out when I started writing The Boss. I’m not even sure where they are now. I tinkered a month ago and got so frustrated with my work that I stopped tinkering. Now I just play with my weiner dog and do what Ilya Kaminsky told me to do—write notes in notebook. And lastly, what are you reading these days? Lots of fiction. The Boss won a California Book Award and I decided to read all the fiction and non-fiction books that also won awards. It’s humbling reading those books and the bios of those talented authors. When I was young, I was so naïve—thinking I could be a great poet. Now I know the truth—great poets are one in a million and on top of that great poets are determined by subjective readers. It’s such a silly aspiration. Now I just want to live a good life. If that life includes poetry, then so be it. If it doesn’t, that’s fine too. Two Poems from The Boss: The boss tells me The boss tells me of the billionaire who likes me who likes my work again this year this year I am safe for another year I can stand by for another year I can align myself with the bystanders who have different standards for another year I can mortgage my heart in monthly installments for another year I can fill my garage with scooters and things with motors like Mona at the end of the hall with her loan and home and college bills who never sees anything in the office never seems to hear anything in the office but her own heartbeat her own term sheet for another year when asked about Mary or Tom or Larry I too can say I never saw anything never saw the boss wind them up and point them towards the edge of the roof before Mary went over the edge I threw down a pillow in the shape of a pet and hoped it landed under her I didn’t stay long enough to see what happened Edward Hopper’s Automat The woman in the automat doesn’t know about the earthquake doesn’t worry about the earthquake in Japan another earthquake in Japan she will be dead by the time the earthquake comes again she is gone by the time the earthquake comes again she can’t be a boss looks too nice to be a boss she looks Japanese she could be a boss why does it matter she is gone the boss doesn’t matter anymore the boss doesn’t make us anymore there’s an earthquake in Japan again the water follows the theories of power the water takes what it wants the water doesn’t want what it wants but takes it anyway the children’s book the old photo the couple having sex on the roof the people want the water to leave the people have no power they want power the people are on the roof of the building the people are no longer on the roof of the building You can read additional poems from The Boss, and order a copy, from Victoria Chang's website.

0 Comments

Born in Kobe, Japan to a Japanese mother and a French Canadian-American father, Mari L’Esperance is the author of The Darkened Temple (awarded a Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry and published in September 2008 by the University of Nebraska Press) and an earlier collection Begin Here (awarded a Sarasota Poetry Theatre Press Chapbook Prize). Coming Close: Forty Essays on Philip Levine, co-edited with Tomás Q. Morín, was published by Prairie Lights Books in May 2013. A two-time Pushcart Prize nominee and recipient of awards from the New York Times, New York University, Hedgebrook, and Dorland Mountain Arts Colony, L’Esperance lives in the Los Angeles area. Let’s begin at the end. Your book closes with the realization that “the life you have chosen” is also “the life / you could not help but choose.” To me, many of your poems have that feeling of inevitability too—that these are the stories you had to tell, the songs you must sing. Did you have that feeling when writing these poems and putting this book together? Most of the poems in my book were written out of urgency—of a deep need to make sense, or attempt to make sense, of an upending, painful, and bewildering experience (the unresolved disappearance of my mother in 1995 while I was a poetry student). The poems span about 12 years, which included long periods of silence. When I’d finally amassed enough poems to create a book-length manuscript, I had more psychic distance from the material and the process felt more task-like at that stage, albeit still infused with feeling. But the making of the poems themselves—yes, that involved considerable emotional investment and, alongside, a more dispassionate editorial self that allowed me to shape them into art. That same poem, “As Told by Three Rivers,” takes place in a hospital, on “the seventh floor of Eye & Ear,” which seems absolutely appropriate since both resonating images and the sound of the line are clearly very important in your work. Does one or the other—the image or the music—come first for you? Images and music are central for me, in my own work and in the poems that I enjoy reading, and admire. When writing, image almost always comes first. Images represent the earth’s body and ground us in the physical world. By the time an image makes its way into a poem, it’s been simmering internally for a good, long while. The music comes as I’m writing and then revising. I was raised by a musician father and was a piano student for ten years as a very young person, so phrasing comes fairly naturally. My early teacher Jane Mead taught me, through her work, the importance of pacing, of music, and how music in poems is also of the body. I know every poet is different, but when I read a poem with (to me) oddly placed or seemingly arbitrary line breaks, I just want to REACH IN and change them! Someone else might read the same poem and have a very different response. Your powerful sequence of poems about your mother’s disappearance, "White Hydrangeas as a Way Back to the Self," feels like the heart of The Darkened Temple. I’m curious to hear how you wrote these poems and shaped them into a sequence. Were you conscious of the shape these poems might take as a collection from early on, or was it a case of diving into the writing and then discovering a shape afterwards, or…? Thanks, Matt. Well… I knew it was going to be a poem in sections pretty much from the start, or that was my intention going in. I knew I wanted to write about a descent and reemergence, but that was about all I consciously had in terms of content. I knew I wanted a lot of white space so each section could float in it, like a bell’s tongue. I had an image, which was inspired by Stevens’s “The Poems of Our Climate”: “The day itself / Is simplified: a bowl of white, / Cold, a cold porcelain, low and round, / With nothing more than the carnations there.” I loved the image of a bowl of clear water and white flowers, and how it made me feel: calm, serene, inward. The carnations became white hydrangeas, a flower that I associate very much with Japan. As for the rest, it was an epic wrestling match, especially trying to convey an emotionally freighted and complex experience in language that wasn’t maudlin, self-pitying, lurid, etc., but still had heft and resonance. It was a long, arduous process of writing, then pulling it back, writing some more, then paring it down, etc. I have to thank Alan Botsford, editor of Poetry Kanto, for publishing all ten sections.  In “White Hydrangeas as a Way Back to the Self,” you write, “My mother disappeared without a trace. // How else to say it?” That’s a line I kept coming back to, because I love how you bring together the lyrical and the matter-of-fact so naturally in your poems. Your poems are meditative in the way they move, yet also tell a story. That’s a tricky combination to pull off. I wonder if you could talk about how you balance those two approaches, and how they come together for you when writing poems. It’s heartening to have you reframe as an attribute what I consider a flaw in my poems, which is my tendency toward narrative. There’s no conscious attempt at trickiness; it’s just how my mind works. All my attempts at elliptical, nonlinear poems have largely been failures. My poems want to follow a trail of crumbs in the mind’s dark wood. Beyond that, I can’t say how I do it. So much, for me, is about feeling as I’m writing, of being deeply attuned to it, then giving it rein, but not too much… always tempering, tempering—that delicate balance (hard!) and the underlying wish to create a world of stillness, depth, and dream. If we think of a single poem as a complete ecosystem, I guess that’s what I’m aiming for. Your poems have a strong sense of place—and I know from our emails that you recently visited Japan. Does going there—or traveling to other places—tend to trigger new poems for you? If so, do you write in the moment, or are those experiences something you’ll come back to later in your writing? Japan is a place that lives in me, as it’s the place of my birth and my mother’s homeland. It’s motherland, in every sense of the word. My visits there have indirectly inspired new poems, often months or even years later. Although after this most recent visit, I was moved to write a (still in progress) poem about Kobe, the city where I was born and which I visited in March after over 40 years away. The city was devastated by the 1995 Great Hanshin Earthquake and has been transformed by new construction and roads, so I recognized very little. When I was there, I felt disembodied and emotionally disconnected. But afterward the impact of my visit, with all its layered meanings, constellated, along with images both imagined and remembered, and I felt moved to begin the poem. As for other places, it depends. I nearly always take notes when I travel—both detailed notes and general impressions. I lived in New York City, a place that is deeply meaningful to me, for three years and wrote copiously in journals, but wrote only a small handful of poems out of that experience. I can’t explain it, but there it is. Often the places in my poems are amalgams of the real and the imagined—a liminal “third”. Like Margaret Fuller’s Italy in my poem “After Reading of the Expatriate Writer’s Death by Shipwreck”—to me, it feels like Italy more than it is Italy, if that makes sense. Is there a story behind your title? How did you decide to call your book The Darkened Temple? I played with several titles, but what circulated through each of them was Engaku-ji, a prominent Zen temple in my mother’s hometown of Kamakura. She grew up right next door to it and played on its grounds as a child. When I visit my family, I have to make at least one visit to Engaku-ji. It is also where my favorite Japanese filmmaker, Yasujiro Ozu, is buried, so there’s a lot of meaning for me there. So there’s the literal “temple”. But “temple” is also a symbol—for the body, the self, a relationship, a world, the mind. I want readers to make their own associations, whether or not they’re aware of the “actual” temple the title, in part, alludes to. Lastly, what are you working on now? What’s next for you, writing-wise? I am slowly writing poems toward a second collection that remains, for now, a distant reality. Art takes time and I’m in no hurry. After The Darkened Temple was published in 2008, I felt enormous relief—I'd been living with some of the poems for so long—and enormous dread, for I really had no idea where to go next with poems, and my professional and personal life had left little space to think about new work. For a time I was in the grip of a “project,” but lately I’ve felt myself letting it go and instead wanting to go back to writing poem by poem, which, of course, requires being in the unknown without an “assignment”. My core themes are still with me, as they’ll likely always be, but I sense an internal loosening that's reflected in these newer poems, which breathe more easily on the page than did many of the poems in The Darkened Temple. That, to me, is a sign of health, and I’m following it. Two poems from The Darkened Temple:

As Told by Three Rivers Eight a.m., up too late the night before learning the nose and throat, the bones of the hand. Rounding a corner on the seventh floor of Eye & Ear, the view from the window takes you by surprise: the city of Pittsburgh fanned out before you, its verdant wedge of land softened by the arms of three rivers, their names alone like music--Monongahela, Allegheny, Ohio-- threading their slow eternal way home, knowing. You think of Naipaul's book, how that distant mythic river in that distant unnamed place reminds you somehow of these three rivers meeting, the purpose in their joined ambition as it should be, how their journey tells the same story, a story of becoming, of knowing one's place in the world. Standing there at the window you see how everything that's come before has brought you here, how it all makes sense, these three timeless rivers moving forward, deliberate and without question, telling the story of the life you have chosen, of the life you could not help but choose. Finding My Mother Near dusk I find her in a newly mown field, lying still and face down in the coarse stubble. Her arms are splayed out on either side of her body, palms open and turned upward like two lilies, the slender fingers gently curling, as if holding onto something. Her legs are drawn up underneath her, as if she fell asleep there on her knees, perhaps while praying, perhaps intoxicated by the sweet liquid odor of sheared grass. Her small ankles, white and unscarred, are crossed one on top of the other, as if arranged so in ritual fashion. Her feet are bare. I cannot see her face, turned toward the ground as it is, but her long black hair is lovelier than I remember it, spilling across her back and down onto the felled stalks like a pour of glossy tar. Her flesh is smooth and cool, slightly resistant to my touch. I begin to look around for something with which to carry her back--carry her back, I hear myself say, as if the words spoken aloud, even in a dream, will somehow make it possible. I am alone in a field, at dusk, the light leaving the way it has to, leaking away the way it has to behind a ridge of swiftly blackening hills. I lie down on the ground beside my mother under falling darkness and draw my coat over our bodies. We sleep there like that. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed