Matthew Thorburn, Poet - Author of Dear Almost

Menu

Renée Ashley grew up in California and lives in New Jersey. She is the author of five volumes of poetry: Because I Am the Shore I Want to Be the Sea (Subito Press Book Prize), Basic Heart (X.J. Kennedy Poetry Prize, Texas Review Press), The Revisionist’s Dream, The Various Reasons of Light (both Avocet Press), and Salt (Brittingham Prize in Poetry, University of Wisconsin Press), as well as two chapbooks, The Verbs of Desiring (new american press award) and The Museum of Lost Wings (Sunken Garden Poetry Prize, Hill-Stead Museum). She has also published a novel, Someplace Like This (Permanent Press). A portion of her poem "First Book of the Moon" is included in a permanent installation by the artist Larry Kirkland in Penn Station Terminal in Manhattan. She has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the New Jersey State Council on the Arts, as well as a Pushcart Prize. She is on the core faculty of Fairleigh Dickinson University’s low-residency graduate programs, the MFA in Creative Writing and the MA in Creative Writing and Literature for Educators. Why prose poems? Do you find that prose poems offer unique opportunities that poems in lines don’t—and vice versa? How do you decide a poem will be a prose poem, rather than in lines? Were the poems in Because I Am the Shore I Want to Be the Sea always prose poems? Prose poems seem such a challenge to me, partially because the form isn’t codified, so if a writer says it’s a prose poem then it’s a prose poem—but if it that poem doesn’t jump up and do something striking and do it well, then it’s just a dollop of, at best, competent prose. I knew there had to be a dynamic that could make it into something I couldn’t construct in another way. And I love the rigor and effect of extreme compression, which I think is one of the keys to making something leap off the page. I wanted the sense of pressure that only justified right and left margins could give—the feeling of being trapped inside a sealed vessel, always at the moment of about-to-explode, no way out—the way we are, so often, in our heads. Or the way I am, anyway. I think of the prose poem as a sort of pressure cooker. That’s what I wanted: no energy leaks and the content volatile, forcing itself against the physical limits of its containment walls. The pressure, to my mind, should be bi-directional: verbal pressure inside pushing out against the rigid, vertical dividing line between text and white space and the visual, structural pressure, the rigid margin of external, white space, pressing back. I seem to know from the onset—or at least believe I do—what impulse is propelling an act of writing. I can hear it in the pacing or see it in the embrace of focus. In Because… I went very consciously after the prose poem form. It took me years to find what I felt was the right mix. Every poem I wrote, for so long, was so obviously lineated that I began to think I was never going to be able to write a decent prose poem. Only when I utterly gave up and felt resigned to just prose and poetry, did I somehow find a way in. My aesthetic was formed as I tried things out—I kept what worked for me and discarded what didn’t. I wrote a lot of essays during that period-of-can’t-make-the-prose-poem-happen, a form that seems to me the polar opposite of the prose poem—it’s so elastic. I’m pretty horrified to admit that a few of the poems that appear in block form in the book were not conceived as prose poems—and this is something I’ve never done before, change a piece into something it wasn’t intended to be. I reworked and pruned them, I think, into better poems in the prose poem shape. (With one exception which is kind of a personal joke.) There were only two or three of these, thank heavens. The after-the-fact shaping is not nearly as satisfying as having the work ignite in the shape it will take in the end. I did it for more cohesiveness on a book-scale rather than on the poem-scale. But I wouldn’t do it again; it’s unnatural and much too convenient a compromise. I’m not certain verbal art from such an impulse is really that plastic. I’m such a hidebound old thing. I find your use of capitalization combined with limited punctuation (that is, no periods) really interesting. For me, this gives your prose poems a very lyrical feel: meaning is sometimes blurred or doubled as thoughts overlap or bump up against each other, and everything moves very quickly. The poems convey the feeling of a mind in motion, moving swiftly from thought to thought. How did you come to this approach—and what is the appeal of it for you? Thank you, Matthew! I’m so happy it reads that way. Yes. No terminal punctuation but question marks and exclamation points. It was about the pressure again. Each phrase or clause needed to run into the next without a full stop; I didn’t want the reader to have a pressureless gap through which to escape; I had to keep up the momentum and the horizontal tensile strength. I used capitalization for the orchestration of sentences or fragments and also to take advantage of some ambiguities that I felt added in a positive way to the pressure-pot. I wanted speed and profluence to compound the pressure that was forcing movement, building momentum, and the sense of being trapped in a thread of thought with no exit. The appeal? The possibility of transferring the sensation of head-as-inescapably-sealed-vessel to paper. That was the ideal I worked towards; I didn’t achieve it exactly, of course, but it’s what I was aiming for. And also, in the book, there’s more white space between the lines than there was in the manuscript: the poems manifested there as much denser and impenetrable. I can understand, though, why the publisher and designer wanted more space between the lines of text. It was difficult to read them in their more compact form; I admit it. How does a poem start for you? In particular, how did “[contemplation within the framework of the dream]” or “[oh yes tomorrow expect the ordinary]” start? And what was your writing and revising process like with these poems? I inevitably begin with a title or first line, an image with a rhythm. I let that beginning generate (sound and association) what follows so that, if I succeed, the dynamic of the poem evolves almost naturally, however strange the poem itself may turn out. All art is artifice, I know, but I’m after a seamless quality that exists in nature. A hybrid, if you will. I rarely, if ever, know where a poem is going to end up, in fact I almost never do, but the poem creates itself from top to bottom, the first line or sentence feeding the second, the second the third, etc. Every once in a while, near the end of a poem. I’ll have to change the order of some lines—or sentences in the case of the prose poem—but more often not. I can’t move forward until what I have feels right—approximate doesn’t do it for me—otherwise I’ll generate something that won’t align well in the end. It’s not an efficient way to work, I know. But it’s the only way I have. Both poems you mention were prose poems from inception, but “[oh yes…]” is a kinder, gentler poem than “[Contemplation…].” That’s the penultimate poem in the book. At that point, I’m trying to ease up on the reader and begin to release him back into the world, not raise his blood pressure. These poems feel like a sequence to me, almost like the chapters of a very succinct novel. It’s a subtle feeling, but it seems like certain themes or ideas or images (or animals) surface and resurface throughout the book. Did you envision writing a sequence or a collection of prose poems from the beginning, or did they gradually build up momentum, or…? It’s funny. Others have said this to me—about a buried narrative— but I never saw it when I was putting the book together, and I haven’t had a chance to just sit down and read it through to see if I can find it. But as for returning themes and images, those I’m aware of. In John Brigg’s book, The Fire in the Crucible, he talks about a writer’s themata, the themes that a writer returns to in her work again and again, and heaven knows I’ve got mine in spades. And that, in fact, may be one of the sources of the sealed-vessel feeling that I so often experience, the I-can’t-get-away-from-me feeling. Those recurring themes are so obvious, in fact, that, years ago, someone I didn’t know at all, came up to me after a reading and said in this really withering tone, “You don’t think much of love, do you?” and instead of thinking, Oh, wow! He’s actually read my work, I laughed. I had to admit it: Nope. No, I really don’t. I hadn’t articulated that to myself before that night. It was like this nova of recognition that burst out of my mouth in the form of a laugh. He was horrified, of course, and probably never read another thing I wrote—but it was such a surprise! But coming back to sequence, I do order poems in a book according to a vague tension-model of Freytag’s triangle, easing in, building intensity, then backing off, and that may be a contributory factor in the sensation of sequence. With the exception of my first book, Salt, in which I was learning what a poem was, I’ve written my books as books rather than eclectic compilations. I’ll have, maybe, five poems toward a new manuscript when I’ll recognize what hobby horse I’m riding into the ground this particular time and I’ll construct the book on that arc. In my second book, The Various Reasons of Light, I was learning how to ground the abstract; that was definitely my conscious project. In my third, The Revisionist’s Dream, I went back to my Comparative Literature roots. The fourth one, Basic Heart, that’s my “nervous breakdown book” though, luckily, I didn’t have one—but it was written during a patch that was about as rough as it’s gotten. And Because I Am the Shore… was definitely meant to be a book of prose poems. I’m far too much a seeker-of-similarities-and-patterns to work randomly; I see a pattern, I begin to recognize some obsession-of-the-next-four-or-five-years, and work with it rather than letting it work against me.  What’s next for you, writing-wise? Are you writing more prose poems? I am! It takes me, on the average, four or five years to write a book. And I’m about half-way through another book of prose poems. I’m also pulling my essays and reviews pulled together into a single book-length manuscript—wish me luck on that one! That’s sure to be a best seller! They’re almost all hybrids: essay/reviews, personal essays/craft essays, interviews. It’ll be ready to send that out by the end of June, I think. I don’t know yet, though, what I’ll do after this next collection of prose poems is completed. I don’t usually recognize the new impetus/obsession until the current project is at least past the half-way mark. Evidently, that’s how I get things finished, one thing nudging the nearly-completed other thing off the road. I may jot down some notes, etc, but I don’t allow myself to focus on anything new until the previous project is bagged up and ready to leave home. It can get frustrating. I work on only one poem at a time. I can, though, work on a poem and an essay at the same time—they’re such vastly different animals that there’s no danger of my crossbreeding them and creating two identical monsters. And lastly, what are you reading these days? I read a lot of essays. I recently finished The Empathy Exams, which was really interesting and beautifully written though I did feel the heavy hand of theme on the book-scale. The individual essays on their own were fabulous. And that same author’s, Leslie Jamison’s, novel, The Gin Closet, which was superb as well. David Grand’s Mount Terminus is an odd, beautiful, and brilliant novel; I finished that not too long ago. Oh! The first volume of My Struggle by Karl Ove Knausgaard kept me mesmerized but I haven’t put my finger on why yet; I’ve got the second huge volume in my pile. Maybe I’ll find out there. Fascinating. Oh! And Lloyd Jones. He’s the most wonderful writer! He’s a New Zealander, but born in Wales, I believe. He’s famous for his novel Mr. Pip which a friend in New Zealand gave me a long time ago and which was surprising and just marvelous. I just finished his biografi and couldn’t put it down! It’s part travel, part creative nonfiction, in which he talks about a trip to and the history of Albania—not something I’d consciously seek out! But I read it in two days and I’m a slow—glacial, really— reader. Could. Not. Put. It. Down. I’ve just started his memoir, A History of Silence. I’ve only read about five pages and I’m smitten. Clean, musical, divine prose. I’ve got two more of his novels in my pile. And I’ve just read Ellen Akins’ new novel-in-manuscript; she writes the most intricate, amazing characters and her sentences are gorgeous, to die for. She’s a remarkable writer and this new book is going to really get a lot of attention, I think. It’s brilliantly strange and familiar. I believed every word. I also listen to a lot of nonfiction in the car (I’m often in the car for long stretches of time). And, of course, I read a ton of poetry. I’ve got poetry books in piles everywhere as well as scattered around the house (just like I do pairs of reading glasses). I like to dip into them. Who’s on my tables now? Let’s see: Alex Lemon, Mary Ruefle, Kathleen Jesme, Rusty Morrison, Cole Swensen, Dennis Nurkse, Martha Collins, Frank Bidart, Saskia Hamilton… I know there are at least half a dozen more lying open around here… I also want to reread Helen Vendler’s books of criticism. She’s astounding: such a lover of poetry and so smart. And Stephen Burt, who slays me. I want to reread Ellen Bryant Voigt’s book on syntax. There’s so much I want to read! I admit it. I’m a book addict. And life’s too darn short! Two Poems from Because I Am the Shore I Want to Be the Sea:

CONTEMPLATION WITHIN THE FRAMEWORK OF THE DREAM Consider the custom of likeness or unlikeness fit as the moon to a sky: let one point light up let it be relative to that The speed of that Let something quite real cry out The dead making themselves known their bodies ill-fit and mostly self-inflicted They change the story A pattern of escalation Of furthering and backing off Embellishment! There is no space big enough for me to speak into about this Any little human thing might act as balm What’s your confession? [oh yes tomorrow expect the ordinary] The dogs sing beautifully over everything beautiful or not—white sleet or white sun—and you have never yet begun with nothing Tell your friends to wait This will take some time Imagine a burned house—steamy sill dampened ash Shingle lintel coal An emptiness spread like soot Can you even begin to comprehend nothing? Posit a negative in a positive mind the idea of no idea expanding? The dark smell of gone of you can’t get this back Consider the stark break between yes and so often—between no and not yet some time Think hypothetical absolute Oh druggery! Oh get me through this Every day dog song and dander jig your approach—such joy! Privilege and you so heart-poor A poverty of fire You yourself consumed But not so simple Never as clear as that Nothing so sweetly entire

3 Comments

Alex Dimitrov was born in Sofia, Bulgaria. He is the recipient of the 2011 Stanley Kunitz Prize from The American Poetry Review, and his poems have appeared in the Kenyon Review, American Poetry Review, Yale Review, Boston Review, Tin House, and Slate, among others. He is the founder of Wilde Boys, a queer poetry salon in New York City, works at the Academy of American Poets, teaches creative writing at Rutgers University, and frequently writes for Poets & Writers magazine. Dimitrov is also the author of American Boys, an e-chapbook published by Floating Wolf Quarterly. He received his MFA in poetry from Sarah Lawrence College, and his BA in English and Film Studies from the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor. He lives in Manhattan. I was struck by the fact that several poems in Begging for It are about America and the last poem in the book, “I’m Always Thinking About You, America,” is even addressed to America. In your work, America—this abstract notion, or this large, complicated country—is made personal through intimate address. Reading these poems made me think of Allen Ginsberg’s famous poem, “America,” though your approaches are quite different. What does America mean for you as a poet—and for your work? Ginsberg is a huge influence and America has remained interesting for me too. Perhaps because it’s always changing, it isn’t fixed, and everyone has such strong opinions about it…even strong ambivalence. I like to think of America as a center full of fire. And I’m drawn to that fire because that’s exactly where I want to put my reader. There are several self-portrait poems throughout the book that help tie it together—but interestingly, they’re all self-portraits as someone else, and in fact as either a fictional character or an actress playing a character. Of course, some people would say every work of art is in some ways a self-portrait, but still I want to ask: what is the appeal of a self-portrait for you? How did these particular “Self-Portrait as” poems come about? My favorite film is Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt. Brigitte Bardot’s character in that film is a complicated one. She’s not a femme fatale, she’s not assertive, though certainly not passive either. She isn’t entirely genuine nor is she inauthentic. I don’t think anyone knows who she is or what she wants. I’m drawn to characters like that because I think they come close to some sort of truth about life. Brett Ashley from Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises and Daisy Buchanan from Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby are also those types of characters, I think. They don’t care if you love them and want you to love them simultaneously. They’re human and unknowable both. To be human is to be unknowable perhaps. And not to pretend otherwise. I was going to write another self-portrait, as Blair from Bret Easton Ellis’s Less Than Zero, but it never happened. Maybe in the future. But I wouldn’t want to repeat myself. I don’t really believe in rules except for that one. You have to change. Begging for It moves forward and flows from poem to poem in interesting ways. How did you go about organizing these poems into a book? I wonder if you could talk a little about the larger structure that these poems inhabit. Was it something you had in mind as you were writing, or did you write the poems first and then find the shape of the book? I had to be in love with every single poem in the book. That was the only thing I was concerned about when I started to think about order. That there couldn’t be any filler. I had to love everything, otherwise why publish it? The order came easily after I got to that point. That took a while though. Four, five years maybe. How does a poem start for you? Specifically, how did “Night Flights” and “To the Thirsty I Will Give Water” start? “Night Flights” I started writing one morning when I was visiting my ex-boyfriend at Princeton. He was going to graduate school there. I remember the scent of his shower took me back to some place from my childhood and that situated me within the aura and time of “Night Flights.” Originally, the first stanza was all about trying to describe that—the being taken there—and then of course I realized that no one really wants to know how you got to the heart. They just want the heart. Or maybe I just don’t want to tell how I got there. Or I have no idea. But I got there. And that’s where I want to stay even though no one can stay there. With “To the Thirsty I Will Give Water,” well, that was written in response to a news story about a man who drove his car into the Gowanus Canal. It’s a poem about redemption and living for love. Even when life is really terrible, I still want to live. And that poem accepts that and also wonders why that is. Why the desire for life. Let me know if you find out…  What’s next? What are you working on now? My second book of poems, a novel, and some other things. Finding the right chairs for my new apartment, most immediately. And lastly: What are you reading—or what have you read recently—that moved you? I went from Truman Capote’s novels to his short stories to his essays to his letters, in that order. And I’ve been seriously reading and rereading him since last August. I think he’s one of the greatest writers of all time. His conversational portraits are some of the best nonfiction I’ve read. It feels even silly to assign them to a genre, they’re so much more advanced than that train of thought… genres. I feel like the last seven years were my Ginsberg and Wilde periods. I’m in my Capote period now. I leave my lion desk lamp on for when I come home late at night, if you know what I mean. Two Poems from Begging for It:

To the Thirsty I Will Give Water Yesterday morning while I read Montaigne a man drove his car into the Gowanus canal. I have never seen a greater monster or miracle than myself, Montaigne wrote in the late 16th century. It was a bright day. The sun forgave no one. Not even the firefighter who first saw the car taken by the water while he was praying, lighting a cigarette, remembering his lover’s face-- what was he doing, what did he think of before diving in? It is not death, it is dying that alarms me, Montaigne tells us. Because he swallowed enough black water during the rescue the firefighter was given two Hepatitis B shots afterward. The man who lost his car was given his life back. We were given Montaigne’s heart which is preserved in the parish church named after him in the southwest of France. We were given more than we can drown. Night Flights One night before my father came she caught me in the yard counting off night flights, keeping tally. The large machines sped over loud and without grace. Each one I pointed to the nearest airport. And those which headed east toward New York or some other city-- they made it. The rest crashed suddenly in someone else’s life. For more info about Begging for It, visit the Four Way Books website and Alex's tumblr.  Victoria Chang’s third book of poems, The Boss, was published by McSweeney’s in 2013 as part of the McSweeney’s Poetry Series. Her second book, Salvinia Molesta, was published by the University of Georgia Press as part of the VQR Poetry Series in 2008. Her first book, Circle, won the Crab Orchard Review Open Competition Award and was published by Southern Illinois University Press in 2005. She also edited an anthology, Asian American Poetry: The Next Generation, published by the University of Illinois Press in 2004. Her poems have appeared in Kenyon Review, American Poetry Review, POETRY, Believer, New England Review, VQR, The Nation, New Republic, The Washington Post, Best American Poetry, and elsewhere. She lives in Southern California with her family and her weiner dog, Mustard, and works in business. These poems are written in a very particular and consistent voice and style that, along with the stanza form you use throughout, really tie the collection together as a larger, cohesive whole. What we hear is an anxious, weary voice delivering what feels like a stream of consciousness (especially give there’s no punctuation) interior monologue. Could you talk about how you came to this voice and style, how it developed? “Anxious and weary,” I like that—that pretty much describes my inner state of existence! I felt trapped in my life at the time, having a bad boss, having little tiny kids, and going through an experience where my dad was having major health problems with strokes and aphasia and generally feeling lost, weary, yet urgent. All these things collided and I just started writing these long-lined, stream of consciousness words that were propelled by language—in a way that mimicked my own feeling of loss of control. As I read your book, I found myself thinking of these not only as individual poems, but also as stanzas in a larger poem which is The Boss. Of course you could say this is true of any book of poems—or it should be. But I’m curious if you felt this way when you were writing and revising the poems—if you saw these poems as parts of a larger whole from the beginning, or at what point you realized you were working on a sequence that would become a book—and if that sense had an impact on how you worked on the individual poems. Absolutely. I was writing towards a series; it was clear right from the start that I was writing more than one of these and they built up slowly, one after the other. Each weekend I wrote them in a Honda Odyssey minivan sitting in front of the same tree waiting for my older daughter to finish a language class. It was the quintessential paradox—a “soccer mom” writing poems in a minivan in Irvine. How surreal. I think I got up to 15-20 of these and started feeling tapped out. I was looking for different entry points into this subject matter and noticed Edward Hopper paintings often took place in office spaces, often enough for me to riff off them. I ran out of those too, so I started riffing off of the same paintings but looking at them differently—those were the most fun to write.  Those Edward Hopper poems are another element that unites the collection. What draws you to his work—and how do you feel his paintings connect to what you do as a poet? I love Hopper paintings—I’m not a sophisticated art connoisseur at all but I visit museums and look at art and sculpture often. I am an uneducated art appreciator. I do love Hopper, perhaps as someone might love Billy Collins. I’m drawn to the mystery of Hopper paintings—the mood, tone. They all seem depressed and the characters in those paintings seem so real to me, caught in a moment by an artist. I love them. How does a poem start for you? In particular, how did “The boss tells me” or “Edward Hopper’s Automat” start? And what was your writing and revising process like with these poems? Was it different from writing the poems in your previous books? “The Boss Tells Me” was based on my experiences working with a really wealthy woman, so wealthy it was almost a surreal experience talking to her about her chefs, her assistants, her life, and her billions. Then she went on to marry another billionaire and the experience became more surreal. She was particularly difficult to work with and it got me thinking about how some people like this get so used to having money and power that everyone around them must be subservient at all times. I was forced to work with this difficult woman because I served her well. It was an interesting trap; I served her so well that she only wanted to work with me! It was like being in jail. If I worked poorly for her, she could get me fired. If I defied her or disagreed with her, she could get me fired. If I spoke up, she could get me fired. But if I didn’t work with her and do a good job, my own boss could fire me. It was a constant washing machine of torture and I felt deathly trapped for years. Until I realized that I control myself and that perhaps culturally, I had learned how to be so subservient due to my family and my culture and I could break that cycle myself. This poem started to grow into my other observations about business people and how they turn a blind eye if others are getting treated unfairly to protect their own jobs or reputations and the woman in the office down the hall came into the poem, as did my own complicit self that ignored another woman who had reached out to me a decade earlier because she was being harassed by my boss. As long as I was doing well, I saw no reason to help this woman. It came full circle, and in many ways I felt like I deserved what I got in the end. Working in business, I tell you, is no walk in the park. It’s like a battlefield out there and you have to fend for yourself. I had to learn all of this on my own, of course, having been raised by parents who neither worked in business, nor were from this country. I’m a tougher cookie as a result, but sometimes I wonder if it would have been easier to be, say, a barista! So much of my 20s and 30s was learning how to be American—my parents brought me up to live in Taiwan. I had no compass and no mentors. I had to learn everything through trial and lots of error. “Edward Hopper’s Automat” started as a riff off the painting where this woman was sitting in an automat (not an office painting, but I was drawn to this painting). The woman in the painting looked Asian to me and the tsunami in Japan had just happened and, for whatever reason, I started writing about the tsunami in the context of this painting. And how in such a terrible situation as a tsunami, one doesn’t really care about one’s boss, couldn’t possibly care about the boss, and how I myself needed to remind myself of the bigger picture so that I could survive whatever trauma that I was going through. The writing process for this whole book was magically different than previous books and because I loved it so much, I find myself unable to write again. I am truly blocked. I want to write like this again but I can’t seem to. I haven’t written in 2+ years and finally sat down recently to write something and the stuff is just a bunch of experimentation and I like it for just that. I am not interested in submitting poems to journals either. I’m not interested in the world of publishing, the people in it, the angling, the climbing, none of it. I am just interested in being a bystander and I am truly loving every minute of being a bystander. I, for once in my life, feel free of the literary world. I truly, truly don’t care. It’s magical. I hope it lasts forever. In addition to being a poet, you’re also a mother and someone who, as your bio says, “works in business.” As a new parent myself, I’m curious to know how you balance those three roles and manage to play all three. And as someone who also works in the business world, I have to ask: do you teach or have any interest in teaching? Sometimes I think that I don’t do anything as well as I think I could if I focused more on one of these things or two of these things. However, other times I wonder if this is the way I am made—without all these things pressing against each other, would I have nothing to say? I often look at poets like Matthea Harvey and think that if I had more time I might write more in other genres, write more work (never as good as hers, of course!), but then I realize she is who she is and I am who I am and the results show who I am. I do what I do because I must like doing what I do. I never chose a life like hers. I must have wanted children, must have wanted to work in business (I love thinking about business), must have wanted to write poetry as a secondary project in my life. Otherwise I would have done things much differently. You can’t envy another person’s life if you didn’t choose it. In terms of balance, I just don’t write. And before The Boss, I didn’t write much either. I do like to read, though, but even my reading competes with poetry—I am voracious and read everything. Poetry is only maybe 10-15% of my reading. I’m just the kind of person who is interested a little in everything. Every day is hard, like today I had so many things to do—a dentist appointment (got my tooth pulled), a kindergarten orientation (of which I missed the memo to bring my kid), a conference call with a foundation CEO on China and energy, work in general, board work related to Kore Press, etc.—that I forgot to pick up a kid in the afternoon! The school had to call me to remind me because I had gotten the time wrong. So yes, every day is a challenge. But I choose to embrace my life for what it is because when it is gone, I will miss it. Yes, I love teaching but no one has offered me a tenured-track position job. I am not famous enough or well-regarded enough to have people knocking at my door and I refuse to apply for jobs. If someone offered me a teaching gig, tenure track, I would consider it. But seriously, I like my work too much. Maybe later, Victoria Chang 2.0. I think I would have to be a better poet first, more respected in the community, get more awards, etc. I just don’t know if I have it all in me. I question my talent, I really do. It is definitely not limitless and I’m not sure it’s that great or worthy. Plus I refuse to move. I love California too much. What’s next for you, writing-wise? It seems like I’ve read quite a few of your prose poems in journals over the past few years—are you working on a collection of them? Or something else? Who knows? Maybe nothing. I’m off the rat race of the literary world treadmill, although now I realize I was never really in it. I just wanted to get in that spinning hamster wheel. That makes me happy. I have no ambitious and that is so freeing. Those prose poems were little experiments and I had written two manuscripts before The Boss and sent them out a few times and they were finalists in the NPS and a few other places and then I just stopped sending them out when I started writing The Boss. I’m not even sure where they are now. I tinkered a month ago and got so frustrated with my work that I stopped tinkering. Now I just play with my weiner dog and do what Ilya Kaminsky told me to do—write notes in notebook. And lastly, what are you reading these days? Lots of fiction. The Boss won a California Book Award and I decided to read all the fiction and non-fiction books that also won awards. It’s humbling reading those books and the bios of those talented authors. When I was young, I was so naïve—thinking I could be a great poet. Now I know the truth—great poets are one in a million and on top of that great poets are determined by subjective readers. It’s such a silly aspiration. Now I just want to live a good life. If that life includes poetry, then so be it. If it doesn’t, that’s fine too. Two Poems from The Boss: The boss tells me The boss tells me of the billionaire who likes me who likes my work again this year this year I am safe for another year I can stand by for another year I can align myself with the bystanders who have different standards for another year I can mortgage my heart in monthly installments for another year I can fill my garage with scooters and things with motors like Mona at the end of the hall with her loan and home and college bills who never sees anything in the office never seems to hear anything in the office but her own heartbeat her own term sheet for another year when asked about Mary or Tom or Larry I too can say I never saw anything never saw the boss wind them up and point them towards the edge of the roof before Mary went over the edge I threw down a pillow in the shape of a pet and hoped it landed under her I didn’t stay long enough to see what happened Edward Hopper’s Automat The woman in the automat doesn’t know about the earthquake doesn’t worry about the earthquake in Japan another earthquake in Japan she will be dead by the time the earthquake comes again she is gone by the time the earthquake comes again she can’t be a boss looks too nice to be a boss she looks Japanese she could be a boss why does it matter she is gone the boss doesn’t matter anymore the boss doesn’t make us anymore there’s an earthquake in Japan again the water follows the theories of power the water takes what it wants the water doesn’t want what it wants but takes it anyway the children’s book the old photo the couple having sex on the roof the people want the water to leave the people have no power they want power the people are on the roof of the building the people are no longer on the roof of the building You can read additional poems from The Boss, and order a copy, from Victoria Chang's website.  Born in Kobe, Japan to a Japanese mother and a French Canadian-American father, Mari L’Esperance is the author of The Darkened Temple (awarded a Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry and published in September 2008 by the University of Nebraska Press) and an earlier collection Begin Here (awarded a Sarasota Poetry Theatre Press Chapbook Prize). Coming Close: Forty Essays on Philip Levine, co-edited with Tomás Q. Morín, was published by Prairie Lights Books in May 2013. A two-time Pushcart Prize nominee and recipient of awards from the New York Times, New York University, Hedgebrook, and Dorland Mountain Arts Colony, L’Esperance lives in the Los Angeles area. Let’s begin at the end. Your book closes with the realization that “the life you have chosen” is also “the life / you could not help but choose.” To me, many of your poems have that feeling of inevitability too—that these are the stories you had to tell, the songs you must sing. Did you have that feeling when writing these poems and putting this book together? Most of the poems in my book were written out of urgency—of a deep need to make sense, or attempt to make sense, of an upending, painful, and bewildering experience (the unresolved disappearance of my mother in 1995 while I was a poetry student). The poems span about 12 years, which included long periods of silence. When I’d finally amassed enough poems to create a book-length manuscript, I had more psychic distance from the material and the process felt more task-like at that stage, albeit still infused with feeling. But the making of the poems themselves—yes, that involved considerable emotional investment and, alongside, a more dispassionate editorial self that allowed me to shape them into art. That same poem, “As Told by Three Rivers,” takes place in a hospital, on “the seventh floor of Eye & Ear,” which seems absolutely appropriate since both resonating images and the sound of the line are clearly very important in your work. Does one or the other—the image or the music—come first for you? Images and music are central for me, in my own work and in the poems that I enjoy reading, and admire. When writing, image almost always comes first. Images represent the earth’s body and ground us in the physical world. By the time an image makes its way into a poem, it’s been simmering internally for a good, long while. The music comes as I’m writing and then revising. I was raised by a musician father and was a piano student for ten years as a very young person, so phrasing comes fairly naturally. My early teacher Jane Mead taught me, through her work, the importance of pacing, of music, and how music in poems is also of the body. I know every poet is different, but when I read a poem with (to me) oddly placed or seemingly arbitrary line breaks, I just want to REACH IN and change them! Someone else might read the same poem and have a very different response. Your powerful sequence of poems about your mother’s disappearance, "White Hydrangeas as a Way Back to the Self," feels like the heart of The Darkened Temple. I’m curious to hear how you wrote these poems and shaped them into a sequence. Were you conscious of the shape these poems might take as a collection from early on, or was it a case of diving into the writing and then discovering a shape afterwards, or…? Thanks, Matt. Well… I knew it was going to be a poem in sections pretty much from the start, or that was my intention going in. I knew I wanted to write about a descent and reemergence, but that was about all I consciously had in terms of content. I knew I wanted a lot of white space so each section could float in it, like a bell’s tongue. I had an image, which was inspired by Stevens’s “The Poems of Our Climate”: “The day itself / Is simplified: a bowl of white, / Cold, a cold porcelain, low and round, / With nothing more than the carnations there.” I loved the image of a bowl of clear water and white flowers, and how it made me feel: calm, serene, inward. The carnations became white hydrangeas, a flower that I associate very much with Japan. As for the rest, it was an epic wrestling match, especially trying to convey an emotionally freighted and complex experience in language that wasn’t maudlin, self-pitying, lurid, etc., but still had heft and resonance. It was a long, arduous process of writing, then pulling it back, writing some more, then paring it down, etc. I have to thank Alan Botsford, editor of Poetry Kanto, for publishing all ten sections.  In “White Hydrangeas as a Way Back to the Self,” you write, “My mother disappeared without a trace. // How else to say it?” That’s a line I kept coming back to, because I love how you bring together the lyrical and the matter-of-fact so naturally in your poems. Your poems are meditative in the way they move, yet also tell a story. That’s a tricky combination to pull off. I wonder if you could talk about how you balance those two approaches, and how they come together for you when writing poems. It’s heartening to have you reframe as an attribute what I consider a flaw in my poems, which is my tendency toward narrative. There’s no conscious attempt at trickiness; it’s just how my mind works. All my attempts at elliptical, nonlinear poems have largely been failures. My poems want to follow a trail of crumbs in the mind’s dark wood. Beyond that, I can’t say how I do it. So much, for me, is about feeling as I’m writing, of being deeply attuned to it, then giving it rein, but not too much… always tempering, tempering—that delicate balance (hard!) and the underlying wish to create a world of stillness, depth, and dream. If we think of a single poem as a complete ecosystem, I guess that’s what I’m aiming for. Your poems have a strong sense of place—and I know from our emails that you recently visited Japan. Does going there—or traveling to other places—tend to trigger new poems for you? If so, do you write in the moment, or are those experiences something you’ll come back to later in your writing? Japan is a place that lives in me, as it’s the place of my birth and my mother’s homeland. It’s motherland, in every sense of the word. My visits there have indirectly inspired new poems, often months or even years later. Although after this most recent visit, I was moved to write a (still in progress) poem about Kobe, the city where I was born and which I visited in March after over 40 years away. The city was devastated by the 1995 Great Hanshin Earthquake and has been transformed by new construction and roads, so I recognized very little. When I was there, I felt disembodied and emotionally disconnected. But afterward the impact of my visit, with all its layered meanings, constellated, along with images both imagined and remembered, and I felt moved to begin the poem. As for other places, it depends. I nearly always take notes when I travel—both detailed notes and general impressions. I lived in New York City, a place that is deeply meaningful to me, for three years and wrote copiously in journals, but wrote only a small handful of poems out of that experience. I can’t explain it, but there it is. Often the places in my poems are amalgams of the real and the imagined—a liminal “third”. Like Margaret Fuller’s Italy in my poem “After Reading of the Expatriate Writer’s Death by Shipwreck”—to me, it feels like Italy more than it is Italy, if that makes sense. Is there a story behind your title? How did you decide to call your book The Darkened Temple? I played with several titles, but what circulated through each of them was Engaku-ji, a prominent Zen temple in my mother’s hometown of Kamakura. She grew up right next door to it and played on its grounds as a child. When I visit my family, I have to make at least one visit to Engaku-ji. It is also where my favorite Japanese filmmaker, Yasujiro Ozu, is buried, so there’s a lot of meaning for me there. So there’s the literal “temple”. But “temple” is also a symbol—for the body, the self, a relationship, a world, the mind. I want readers to make their own associations, whether or not they’re aware of the “actual” temple the title, in part, alludes to. Lastly, what are you working on now? What’s next for you, writing-wise? I am slowly writing poems toward a second collection that remains, for now, a distant reality. Art takes time and I’m in no hurry. After The Darkened Temple was published in 2008, I felt enormous relief—I'd been living with some of the poems for so long—and enormous dread, for I really had no idea where to go next with poems, and my professional and personal life had left little space to think about new work. For a time I was in the grip of a “project,” but lately I’ve felt myself letting it go and instead wanting to go back to writing poem by poem, which, of course, requires being in the unknown without an “assignment”. My core themes are still with me, as they’ll likely always be, but I sense an internal loosening that's reflected in these newer poems, which breathe more easily on the page than did many of the poems in The Darkened Temple. That, to me, is a sign of health, and I’m following it. Two poems from The Darkened Temple:

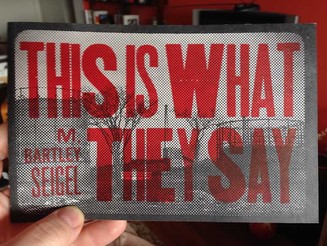

As Told by Three Rivers Eight a.m., up too late the night before learning the nose and throat, the bones of the hand. Rounding a corner on the seventh floor of Eye & Ear, the view from the window takes you by surprise: the city of Pittsburgh fanned out before you, its verdant wedge of land softened by the arms of three rivers, their names alone like music--Monongahela, Allegheny, Ohio-- threading their slow eternal way home, knowing. You think of Naipaul's book, how that distant mythic river in that distant unnamed place reminds you somehow of these three rivers meeting, the purpose in their joined ambition as it should be, how their journey tells the same story, a story of becoming, of knowing one's place in the world. Standing there at the window you see how everything that's come before has brought you here, how it all makes sense, these three timeless rivers moving forward, deliberate and without question, telling the story of the life you have chosen, of the life you could not help but choose. Finding My Mother Near dusk I find her in a newly mown field, lying still and face down in the coarse stubble. Her arms are splayed out on either side of her body, palms open and turned upward like two lilies, the slender fingers gently curling, as if holding onto something. Her legs are drawn up underneath her, as if she fell asleep there on her knees, perhaps while praying, perhaps intoxicated by the sweet liquid odor of sheared grass. Her small ankles, white and unscarred, are crossed one on top of the other, as if arranged so in ritual fashion. Her feet are bare. I cannot see her face, turned toward the ground as it is, but her long black hair is lovelier than I remember it, spilling across her back and down onto the felled stalks like a pour of glossy tar. Her flesh is smooth and cool, slightly resistant to my touch. I begin to look around for something with which to carry her back--carry her back, I hear myself say, as if the words spoken aloud, even in a dream, will somehow make it possible. I am alone in a field, at dusk, the light leaving the way it has to, leaking away the way it has to behind a ridge of swiftly blackening hills. I lie down on the ground beside my mother under falling darkness and draw my coat over our bodies. We sleep there like that.  The Alphabet Not Unlike the World (Milkweed, 2012) is Katrina Vandenberg’s second book of poems. She is also the author of Atlas (Milkweed, 2004) and co-author, with Todd Boss, of the chapbook On Marriage (Red Dragonfly Press, 2008). She teaches in the Creative Writing Programs at Hamline University in Saint Paul, Minnesota and lives four blocks from campus with her husband, novelist John Reimringer, and their daughter Anna. Q: How did The Alphabet Not Unlike the World come together as a book? Did you set out to write a book of poems about the alphabet? Or did you write certain of these poems and then begin to see the shape a collection might take around them? I’m curious to hear about your process. A: Slowly. Partly because I wrote it in a six-year period while I was both trying to start a family, and publishing and promoting my first book, Atlas. The publication of Atlas had been swift, sudden, and unexpected; the child-bearing was slower, anxiety-inducing, and involved miscarriages, surgery, and hormone crashes. The book had two false starts. At first it was meant to be about my first partner Tim’s trip to Ireland after we graduated from college. I went to Ireland alone the summer before Atlas came out and, using his old travel journal, retraced his steps. Within a week there I knew I couldn’t write that book; it was his trip, not mine. Atlas was a book about grief, but when I published it, I closed the door on that part of my life. Then, the book was about adolescence and what it means to be a girl. It wasn’t until I was at the Amy Clampitt House in Lenox, right after we met at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, that I began to write the alphabet poems; the bulk of the book was written in late 2008 and early 2009. So for me, a big challenge was trying to figure out how all these poems from three disparate projects fit together, if they did at all. There is an enormous cast of characters. Finally I saw a connecting thread: this is a book about forgiveness. I owe my first editor, Jim Cihlar, for helping me structure it in a way that created a coherent narrative. He had suggested that the first section be a sort of précis, showing the arc of the book in miniature. Q: There are several ghazals throughout the book, which help tie it together—and which are all letter poems, like “Prologue: A Ghazal” and “Z Ghazal,” the two that bookend the collection. What drew you to this particular form? A: When I got interested in writing about the letters’ history as pictures, I initially wanted to write all the letter poems as ghazals. The form felt right, and I liked that it came from the same part of the world that the letters did, though the form isn’t as old as the letters themselves. After writing a few, that window closed, and the alphabet poems started pushing into other directions, though if you look at the Q poem in particular, you can still see the ghost of the abandoned ghazal. Probably an entire book of alphabet ghazals would have been obnoxious. Q: One of the things I love about your poems is the way you include so much lived life and vivid visual detail. The poems are always about something—actually they are always about several somethings. I’m wondering, how does a poem start for you? Are there certain things that will trigger a poem or give you a way into a new poem? A: Sometimes it’s a line: “A Ghazal” started with my getting this line stuck in my head: “it is strong enough to pull the train of letters through the poem.” The poem “X” began with the phrase “I promise to write a poem about forgiveness. Even if this, even if that.” Other times, I get a prickly feeling in my head or a queasy feeling in my gut, and I know that I want to spend some writing time exploring an image or a memory or a word. I give my students prompts and poem ideas, and sometimes try them out myself — in particular, we sometimes play a game in which we force metaphors between two things we’ve been meaning to write about, just to see what happens — but really, my best poems begin in a way I can’t control and can’t explain. Mary Ruefle has an essay in Madness, Rack and Honey about how little is said about where poems begin, because no one knows. I can’t teach my students how to have that prickly feeling, only to respect it. Q: On a related note, these poems—especially the ones about individual letters, such as “X”—are filled with facts, trivia and snippets of history, yet this information feels entirely owned and embodied in the poems. There’s never that research-paper feeling of trying to squeeze all the relevant info in. I wonder if you could talk about what part research (however you’d define that) played in writing the poems, and how you translate research into poetry. A: Some of that is the kind of person I am, one who likes to know a little bit about a lot of things. In general, I think that, when it comes to research in a poem, one of two things has to happen. Either you have to have known the piece of information long enough that it has time to compost inside you and become yours. Or, the revising of a poem with research in it has to involve a lot of subtracting — pulling out and pulling out the extra show-offy bits. It’s surprising how small a kernel of research in a poem needs to be. But it also has to be the right snippet, so when I’ve used research, I’ve found that I progressively chisel away at it. I’m a slow writer, which might help in this case.  Q: In addition to being a poet, you’re also a mother and a teacher. As a new parent myself, I’m curious to know how you balance those three roles and manage to play all three? A: Badly? Or maybe it’s just always a work in progress. I talked about this a bit with the poet Molly Sutton Kiefer, on her wonderful blog Balancing the Tide: Motherhood and the Arts. The interview is here. But when I told her all of this, my child wasn’t walking yet, so I didn’t know the half of what it meant to teach, write, and parent a little person whose job is to get into everything. Students, writing, family — any one of these is willing to take everything you can give and then some. I’m a big list maker, I get up earlier than I used to, I’m willing to shell out as much as I can afford for child care. I have a spouse who truly co-parents. I’ve also had to acknowledge in the last 2-3 years that because my family is at the center of my life, I am willing to take the hit that comes from sitting on the sidelines a bit more, poetry-wise, while my daughter is small and needs me. I don’t think it anti-feminist or anti-art. I do think it’s very human, and my writing and teaching will ultimately be rewarded by it. Q: Lastly, what’s next? What are you working on now? A: These things never make sense when you describe them instead of just showing them to someone — who said that it’s impossible to paraphrase a poem? — but I’m working on a piece called Conservatory. It’s in the stage of its development where I’m not totally sure what it is, a book-length poem, a piece that bends genre, or both. It’s inspired by the source of our sanity as parents of an active toddler who lives in the frozen north. In the Marjorie McNeely Conservatory in Como Park, it is never winter. Two poems from The Alphabet Not Unlike the World: X I promise to solve for X. I promise I will write a poem about forgiveness. Even if it is April and another college boy has drowned in the Midwest. XX means “girl,” XY means “boy.” A serial killer, some say. Others: The boys are drunk and we have rivers. We also have rails, trestles in fields of corn, steel mills. A restless moon, a horizon you can see clear to, crows on telephone poles like Xs strung together. As unfertilized eggs we all begin as XXs. Even if we have lost dozens in the Mississippi, eight in LaCrosse alone, this poem is about forgiveness. It tries to solve for X—X the cross, X the Christ, X to X things out. The boy in Saint Cloud. The boy at Saint John’s, where the monks bake bread and copy the Bible by hand. When the moon is dark and new. X the unknown, X for times. X for ten, for more than ten. On the Web site’s map, the gravestones marked with little crosses pop up along I-94 like crocuses, until you can’t see one for another. It is Easter. The red-winged blackbirds are coming back to Minnesota, their wings’ tips feather the river along. The river is a swish of calligrapher’s ink, the boys are drowning inside the X-- X for stranger, Mr. X. I love the Mississippi, how it can mirror back the world without us in it. How it keeps insisting to the bluffs, Sandstone-- river—limestone—river—shale—river—river. The river of thoughts about Mr. X has worn through us almost that long. XO, I kiss you, the letter is sealed. I do not want to die without lifting a child of my own from the water. Earthworms It is raining again this morning. I remember it rained then, too, that summer morning we lay crosswise on the bed, the curtains grazing our heads, quickened by the damp wind. Outside, the earth was opening and the worms had surfaced, blind. They have eaten every bit of dirt that makes our yard. In bed at night, we turn the story of the child whose heart we never heard, the child who never heard rain. And we don’t care, we let it surface—we open ourselves, from time to time, to happiness. Don't you find, after finishing a good book, that you'd like to ask the author a few questions and continue the conversation? Me too. This is the first in a series of conversations I hope to have with the authors of books I enjoy reading. I call this What are You Reading? because whenever I talk to a friend that's the question we always ask each other. Here are my answers to that question, the books I'm enjoying and recommend you check out.  First up is This is What They Say, a collection of prose poems by M. Bartley Seigel, published by Typecast in 2012. Seigel is the founding editor of the critically acclaimed literary magazine [PANK]. He lives, writes, and teaches in Houghton, Michigan, where he is assistant professor of creative writing and diverse literatures at Michigan Technological University. This is What They Say is his first book. Q: How did This is What They Say come together for you? I’m curious about how these poems evolved into a book. Did you set out to write a collection of prose poems, or did you write a certain number and begin to see a larger arc to the work, or…? A: A certain number materialized and then momentum took over. Jen Woods at Typecast was instrumental as an editor, as well, helping to cut through a lot of the fat I'd built up on the page, get down to the bone. I suppose a collection was always in the back of my mind, but the poems that appear in the book were mixed among many others published in lit mags over the years. It was very slow and organic, bringing the thing into focus. Q: I’m also interested in the choice of the prose poem as a form. Were these always prose poems, or did you try breaking them into lines at any point? Did you feel the form enabled you to do something you couldn’t do in lines, or couldn’t do as effectively? A: Some started as prose while others were broken down. I settled on prose as a form that cut through some of the perceived bullshit of poetry, by which I mean the artifice that keeps many readers at bay. I write a lot about very bare bones people in bare bones circumstances and burying that under a heavy handed prosody just never felt right to me, at least not with these particular poems. Q: The book is dedicated to the “people and places of Montcalm County, Michigan, from a time when I called it home,” and one of the things I love about this collection is the strong sense of a lived environment—a specific landscape and culture, a tangible place. As the dedication suggests, there’s also a kind of looking back going on in the poems. Did you need that distance of time and space in order to write these poems? And what was that looking back like for you as a poet? A: I dwell a lot in memory and mythology and the particular kind of fantasy those two combine to form, particularly in my poems. I've always been very taken with the idea of nostalgia, especially in its original sense, combining ruminations of home with a certain pain or anxiety or melancholy or loss, something more akin to phantom limb syndrome than to any kind of sentimentality, but always, always deeply romantic. And yes, it takes some time and distance from a period and place for that thing to build, I suppose. Q: As someone fascinated by narrative strategies and choices, I also noticed right away (and admire) the fact that the book is written from the first-person-plural point of view. It’s a “We” speaking to us—and in some ways for us—in these poems. Could you talk about this choice and what it does for the poems? A: I often find emerging and contemporary poetry very galling due to its deeply myopic confessional. I often find myself thinking, as I read a poem, who cares about this BUT the poet talking to herself? No one. Sure, sure, finding the universal in the personal and all that, but at a certain point it's just the worst kind of narcicism. No wonder poetry is in the straights it's in (though to be honest, I'm ok with poetry's "straights"; it seems to be doing quite well despite all the hand wringing to the contrary). I wanted to harken back to my perceived sense that poets used to speak for people other than themselves (that's probably not even really true, right?). "We" is a pretty simple way to do that. Then, of course, there was a sense in the book that the people to whom I'm speaking and speaking of aren't often allowed to speak for themselves and I wanted to play with that, turn it on its head, as much as I could.  Q: In addition to being a writer, you’re also a father, a professor, and editor of the literary journal [PANK]. As a new parent myself, I’m curious to know how you balance all of these roles and manage to play all four? When and where do you find time to write? A: I'm not writing much at this exact moment, to be honest. And my wife is a writer/professor/parent/spouse, too, which is to say, most days, we barely keep shit from burning down around us, and that's good enough. I turn 40 this year. I'm going to be living in Estonia for a year starting in August, teaching at Tartu University. This spring, I'm mostly doing yoga, painting rooms in my house, playing ukulele, rearranging my furniture, teaching, editing, cooking earthy meals involving a lot of lamb and butter, drinking red wine, sitting around on my ass in candlelight, watching the new season of Vikings, reading, and engaging as deeply with my marriage and my kids as I can, looking forward to the upcoming mountain biking season. The writing will either happen and be a part of that or it won't. I'm cool either way. Q: Lastly, what’s next? What are you working on now? A: Besides moving to Estonia next academic year? I want to build a sauna in my basement. I'd like to start keeping chickens again; I really enjoyed that when I did it before. I'd like to get another dog; my last dog died last year. Writing-wise, I've got a batch of little gritty love poems I should probably shop around. And there's been an essay collection percolating for a couple years I should probably crank on. Honestly, though, I don't know. We'll see, I guess. Two poems from This is What They Say:

We lie sullen in the dark, arms thrown over our eyes, breathing in the other's breath. It takes no small process to dislodge ourselves from each other, our sheets, to cross the floor barefoot without upsetting floorboards or children. Then kettles, faucets, stove tops, cups, refrigerators, cartons of bad milk, all our little explosions. This is a kind of seduction, too, though we seldom see it. We are all paper dolls. We are all scroll work and the creative use of light. Out the window there's fog on the hills while inside there's the smell of chicken bones, cat boxes, kerosene, the coffee burning. In our pubic beards, the smell of each the other's body. But all we can think of is avoidance and even this thought-crab crawls out our ears, out through our half open windows while we stand there, dead in our skins, hands limp at our waists, watching our dreams disappear into the darkening trees. After the terrible argument we will make love and afterward lie sullen on the bed, our bellies down, heads turned away. Life is all beyond us, and we will get up without speaking, without so much as a sigh, and go into the bathroom to draw a warm bath. We will listen to the sound of the splashing water. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed