Matthew Thorburn, Poet - Author of Dear Almost

Menu

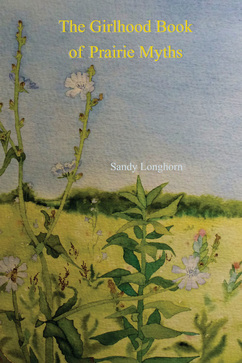

Recently I had the opportunity to interview Sandy Longhorn for Ploughshares. Sandy is the author of three collections of poems, Blood Almanac (Anhinga Press, 2006), The Girlhood Book of Prairie Myths (Jacar Press, 2013) and The Alchemy of My Mortal Form (Trio House, 2015). She teaches at Pulaski Technical College in Little Rock, Arkansas, and co-edits Heron Tree, “a journal of online poetry, bound annually.” From the importance of a sense of place, to thoughts on how one book leads to the next, to the practicalities of being a working writer (for example, getting your butt in your chair every day, so you can write), our interview covered a lot of ground. Here’s the second part of our conversation (and be sure to check out part one as well): MT: A sense of place and being in a landscape seems very important to your work. Could you talk about how place influences your work? Do you feel that you write from a particular place? SL: I have to credit my time at the University of Arkansas, where I earned my MFA, as the place and time where regionalism came into focus for me. The program at Arkansas is four years, which was instrumental for me, as I didn’t find my voice until midway through my third year when I began writing poems of place set in the Midwest. As a Southern program, most of the writers teaching at Fayetteville at the time were steeped in place (Miller Williams and Davis McCombs, for example). However, it was fiction writer Skip Hays who once said to me that there could be no Faulkner, no Garcia Marquez from the Midwest since we were all “just a bunch of tight-lipped Methodists.” Having loved the highly imagined worlds of Garcia Marquez for years, I took that as a personal challenge and began to write poems from the Midwest that would use the type of gorgeous language and imagination that I associated with some of my favorite Southern writers. I will confess that as soon as I moved away from the prairie of the Midwest (eastern Iowa to be exact) and lived in Colorado first, then Massachusetts, I became a stalwart booster of the area. In fact, I never realized how strongly I identified with the place until I lived elsewhere. Regardless of all of this, my first two books contain poems that could not have been written without my trips back home. In these trips I consciously tried to absorb that sense of place, even taking notes on the landscape and the ways of the people to bring back to Arkansas and use when I sat down to write. In this way, place becomes a character itself in many of my poems.  MT: After reading and enjoying your first book, Blood Almanac (Anhinga Press, 2005), I was curious to see what you’d do next. I think it’s interesting to look at how a poet’s second book builds off of, responds to, or may be completely different from the first. Could you talk about how The Girlhood Book of Prairie Myths and Blood Almanac relate to one another? SL: I’ve hinted at some of this earlier, so I’ll try not to be too repetitive. Needless to say, there is a fallow period, for me, between books. Yet, some of the oldest poems in The Girlhood Book answer directly back to Blood Almanac. For example, “Having Been Begotten,” is a direct descendant of “Labor Day on the Bremer Blacktop,” although I seriously didn’t see the connection until the first time I read “Having Been Begotten” for an audience. The Girlhood Book had a bit of a long history, and I’m indebted to Jacar Press for publishing it. The poems included changed many times over the six or seven years of its writing, with the tales and saints being some of the “youngest” poems in the book. At some point, I knew I needed to go beyond the self and find out what more there was to discover about the Midwest. You may notice that the last section of The Girlhood Book seems the most autobiographical, even down to titles such as “Autobiography as Cartography.” This section probably could have been included in Blood Almanac, had I written the poems early enough to include them. The other sections, I do see as distinctly their own. MT: How does a poem start for you? Specifically, could you talk about “The Interior Weather of Tree-Clinging Birds” and “Cautionary Tale of Girls and Birds of Prey”? How did each of these poems start, and what was the writing and revising process like? SL: First, my writing process is all about BIC (butt in chair). I don’t wait for the muse to strike. Instead, I’m at the desk at the same time on the same days (as best I can), trying to write. So most of my poems begin from some form of daily prompts. My favorite is the word bank. For this, I grab the books closest to me and skim for great nouns, verbs, and sometimes adjectives. I put these down randomly in my journal, being messy on the page. Soon links begin to form and words spark off of each other, so that I draw circles and arrows and stars on the page of jumbled, “stolen” words. Usually, a line suggests itself and I go from there. My revision process is largely one based on sound. I read out loud as I draft, and I read out loud, over and over again, as I revise. Sometimes, it comes down to changing one word and then re-reading a poem from the beginning until I hit another sonic glitch. Word choice, punctuation, and line breaks all come into play, and all are questioned in the revision process. Going back through my journals (yes, I date every new day of writing), I found the sparks for “The Interior Weather of Tree-Clinging Birds” on January 16, 2009. I did not use the word bank for this poem, so I only have the barest of clues. I have written the phrase “oracle of ice & snow” and I’ve scribbled these lines: “On the coldest day of winter / consult the interior weather / of tree-clinging birds.” I suspect two things. First, I was using an Audubon bird guide a lot in my writing at the time, and Audubon uses “tree-clinging” as one of its categories for types of birds. Second, if we could access the weather report from the 15th, I’d bet that the meteorologist on Channel 7 said something about the 16th as a possibility for the “coldest day of winter” that year. There are more lines scribbled on the page that tease out phrases like “my oracle of icicle and snow” and “ a future told in cast of seeds / and feathers tipped with pitch.” In my process, as soon as enough lines come together to gain critical mass, I switch to the computer to draft. At some point, I must have seen “the interior weather of tree-clinging birds” as more of a title than a line, and I expanded on the idea of oracles. I do remember switching “oracles of ice and snow” to “oracles of icicles and snow” because of the “ck” sounds within the words. I also remember revising “a future told in cast off seeds” to “cast off hulls” for the sound, and accuracy, as well. *One side note, if you’ll permit me. I was so in love with the sounds of this poem, that I kept putting it at the front of the collection. It took a very astute reader of the book as draft to explain to me that it had to go later because I was rushing the audience and they weren’t prepared for the themes in the poem yet. Sometimes, we are too close to our work to see it clearly. It looks like “The Cautionary Tale of Girls and Birds of Prey” was written on June 10, 2011. Let me be clear, by “was written,” I mean the first draft. I usually continue to tinker with a draft over several weeks, and sometimes months, after I’ve gotten a sense of it as a whole. I do have to get the “whole” of it down in one sitting, though, or I tend to let a draft wither away. So, this cautionary tale was written at a time when I was “in the groove” of writing the “tales” in the book. I didn’t need much prompting at this point and very little word gathering. Instead, I had a strong sense of my “girl” and the struggles she faced. My notes do say that I used a list of “Midwestern notes” that I’d brought back from a trip up home, with “hawk” being the kickoff for this poem. While I won’t say that the tale drafts came “easily” at any point, I will say that there wasn’t as much groping for the drafts. There was, however, much more tinkering at a later point, as I tried to blend my focus on sound with the straight-forward narratives.

1 Comment

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed