Matthew Thorburn, Poet - Author of Dear Almost

Menu

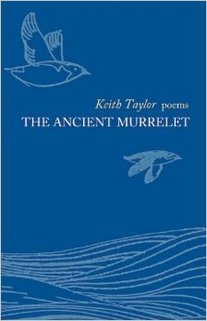

Over the years Keith Taylor has published some fourteen volumes of poetry, short fiction, translations, and edited volumes. His most recent chapbook is The Ancient Murrelet (Alice Greene and Co., 2013), and his most recent full length collection of poetry was If the World Becomes So Bright (Wayne State University Press, 2009). In 2011 he published the anthology Ghost Writers, co-edited with Laura Kasischke (Wayne State University Press), and an extended chapbook, Marginalia for a Natural History (Black Lawrence Press). Over the last few decades his work has appeared in a couple of hundred journals, magazines, newspapers and online sites, here and in Europe, including The Los Angeles Times, Hanging Loose, The Iowa Review, The Chicago Tribune, Poetry Ireland Review, The Sunday Telegraph, Pank, The Southern Review, etc. He has had fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Michigan Council for the Arts. After working at several occupations, some dumb, some great (like working as a bookseller in Ann Arbor for 20 years), he settled into his role as coordinator of the undergraduate writing programs at the University of Michigan, where he also works as the Director of the Bear River Writers’ Conference and, currently, as the Poetry Editor for Michigan Quarterly Review. He has had fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Michigan Council for the Arts and Cultural Affairs, and extended residencies at the International Writers’ and Translators Centre on Rhodes, Greece and at Isle Royale National Park. You’ve published a number of chapbooks and books of poems, most recently the chapbooks Marginalia for A Natural History and now The Ancient Murrelet. Would you talk a little about the appeal of chapbooks versus books for you as a writer? Do you approach them differently when it comes to assembling your poems into larger wholes? Right from the beginning of my publishing life, I’ve enjoyed that moment when some of the poems written in a particular moment assume a kind of coherence. They crystallize a thought, an image, an approach to the poem, or a set of experiences that seem to belong together. The group is usually small (although my chapbooks have varied in length from 10 poems to 35 poems). The little books often explain me to myself as they take shape. But they are small moments. The same poems can assume a very different shape and feel in the context of a larger book. The sweep there is going to be over many years – a decade, a lifetime – and I don’t need to dwell on that single moment or image any longer. It has become part of an intellectual, emotional or autobiographical mosaic. Even though the poems in my chapbooks often get other incarnations, I always make sure there is something that gets published only in that form, so those few readers who have made the effort to find the tiny books will have something that exists nowhere else, even if they don’t know it. On a related note, how does a collection come together for you? Did you know as you were writing them that these poems would fit together as a chapbook – or was that a decision made later after the poems were written? The two recent chapbooks you mentioned came in the very different ways you describe in your question. I knew I wanted to write Marginalia for a Natural History several years before I started it, and I knew I wanted to dedicate it to my friend, Jerry Dennis, a fabulous Michigan essayist and outdoors writer who knows our lakes and streams as well as anyone. I started finding the subject for the poems when I began teaching at the University of Michigan’s Biological Station. There I hung out with field biologists and was always listening to their conversations and their research talks. I stumbled onto a very rigid little form – 8 lines long by 9 syllables per line – that seemed to work well for capturing nuggets of information, and then freed me up to put other experiences into the form. I wrote about 70 poems and picked 35 of them for that little book, trying to create a kind of arc. The Ancient Murrelet came after, when I wanted to free myself from that unforgiving form. I went through a moment when I was rereading Jean Follain (for a review I never wrote, I’m ashamed to say) when my daughter, then about 20, was doing a lot of traveling. I was moved to do some poems, under the influence of Follain, around her traveling, and that brought up memories of my own years on the road. I had also written some poems about birds and animals who found themselves in the wrong places – and suddenly these two things seemed to be finding coherence in a loose sequence about something we might call “home.” I’m still not sure I can actually name the place I arrived at in that little book, but it feels quite clear to me.  You’re a writer of moving, beautiful, sometimes haunting poems about the natural world. But I also notice in this collection how technology is creeping into the picture – for instance, the ancient murrelet found by “following // clear directions on the internet,” and the night-vision camera and DNA testing in “In the Presence of Large Predators.” Is that something you were conscious of? And does the ever-greater role technology plays in our lives impact how you write about nature? Oh, yeah, I’ve noticed! You can’t be a writer of my age (I’m 62 now) and put “internet” in a poem without stopping to think about it. And it’s physically harder for me to go into the woods now, so a couple of gadgets help. This changes things, completely, and not necessarily in a good way. I’ve started using a collapsible walking stick from REI to take the pressure off my knees, for instance. Oh, I hate admitting it. So, yes, the technology we take into the wild to help us measure and understand the natural world changes our experience of it. Of course, it probably doesn’t change it as much as when we discovered the spear; certainly not as much as when the gun became portable. The scientific apparti we take with us are necessary to understand the changes we have forced on the environment and will be absolutely necessary to help us live in this changed world. I’m pretty sure there will be poems there, even if I wonder why there doesn’t seem to be many about climate change, yet. Why is that, Matt? Speaking of technology, I want to shift away from The Ancient Murrelet for a moment to ask about your ongoing experiment with writing poems on Twitter. What has that experience been like? Any plans for those poems to have a life beyond Twitter, perhaps as a chapbook? I’ve written 37 of those little Twitter poems in the last seven months. I really don’t know anything about Twitter and I know I’m not doing it “right,” although I’m not sure that word applies. I’ve always liked short poems – haiku, epigram, aphorism. The 140 character constraint seemed like a useful albeit arbitrary limit to work with. I liked the fact that I could do one on my phone while I was far away from my computer. It feels kind of fun to sneak one into the technological lives of a couple of hundred people. But I’m not sure very many of them are very interesting. Maybe 3 or 4. A couple of friends have talked about doing a technology mash-up and printing 10 or so of these twitter poems in a very limited letter-press edition. A 21st century form preserved on 19th century technology. There wouldn’t be more than 100 copies, though, so it would be a tiny life. Still, I like it.  How does a poem start for you? Specifically, could you talk about “When the Girls Arrived in Copenhagen” and “Chasing the Ancient Murrelet”? How did each of these poems start, and what was the writing and revising process like? “When the Girls Arrived in Copenhagen” was the first of those poems written under the Follain influence. That quiet sense of distance coupled with the blurring of historical moments feels very Follain-esque to me, although that may be a completely subjective response to that great writer of small, polished gem-like poems. I was also close enough to the formally rigid poems in Marginalia that I wanted to write a very different line, free and easy. I’ve also liked Michael Dickman’s line since I started reading him – that big variation in line length, which I’ve also admired in Diane Wakoski’s poems for a long time. I know you can’t tell it, because I don’t seem to be able to rescue myself from the blocky looking poem, but that was in my mind when I was writing that poem. I still want to play with that. Oh, and yes, my daughter was out there in the world doing some very interesting traveling. I thought of her often. “Chasing the Ancient Murrelet” was different, much more intellectually driven. There was that bird, so bizarrely out of place in the mouth of the Saint Joseph River on Lake Michigan, and I could find it only because of directions from the bird-lists. All very bizarre. Its place there, and its almost certain death in a place it didn’t belong, recalled the sense of my aging, my resignation to the limitations of desire (the beautiful young woman running on the beach – oh, yes, I know it is completely a “male-gaze” moment, and I wish it weren’t.). That river itself, which was important to a part of my life, when I went to high school in South Bend, Indiana, where the St. Joseph River turns. In my experience of that city, it was desperately post-industrial and seemed to have lost its sense of itself for a while. So all of that was coming together in that poem. It, too, ended up being controlled by an arbitrary but demanding syllable count. It was just my way to try to shuffle all of that material which seemed to go together in my mind but which might have been uncontrollable. “In the Hard Months,” the last poem in the chapbook, confesses to a shortage of faith—or perhaps it’s more a desire for a deeper faith. You write of a wish to believe “…that the poem / will come again, confident / and supple in its moment on the page.” What a last thought to leave with the reader! For that matter, I also see the ancient murrelet – out of place in its surroundings, its future uncertain – as a symbol of the poet (as well as of course being just this particular bird you describe so wonderfully). All of which is to say: How do you keep going as a poet, and stay interested and engaged? And what do you see as the poet’s place in the world? You’ve nailed it, Matt. How do we keep going, stay interested and engaged? It gets even easier as one ages to be overwhelmed by the fragility of poems. The way they are ignored. The way most readers would not read them the way they must be read. I think that on some days, and then on others a poem will come back to me, will sing in my imagination, will help me understand something I see or experience in the lived world. I am reminded of their resilience. Their strength. I can get depressed by the sameness in contemporary poems. About easy unexamined attitudes. And suddenly some new poet in a first book just blows me away, is clearly writing poems to save her life, and along the way helps her readers too. A poet I wish the whole world would read. Urgent, necessary – and not in some blurby sense. Actually urgent. That excitement can be amazing when it comes again. It’s hard sometimes being around smart young poets (say in a good MFA program, like ours at Michigan). It’s hard to bite my tongue when they are all enthused by some literary fashion that will clearly pass in five years. But I remind myself that this is what we all do, in all the arts: we enter our contemporary artistic stew and we define ourselves with or against our contemporaries, and we move past all that to our place in the bigger picture. So the young poets keep me reading, keep me exploring, even in things that puzzle me or prove ephemeral. The poet’s place in the world? I don’t want to get too fatuous here. And there is indeed the distinct possibility that the world no longer needs what we provide. But, yes, truly, I think the poet’s effort to find an intense language that mediates between the phenomenon of the world and the exigencies of intelligence and imagination, continues to be necessary. I even think that role is still acknowledged by many people in the world, even if they don’t read poetry or find it only obliquely. But sometimes it is tough to convince myself of that. What are you working on now? What’s next for you? I would like to put together a little regional book, very specific to my tiny area of southeast Michigan. It would be a book of poems and prose pieces, even of journalistic things I’ve written about the Huron River. We’ll see. I am trying another chapbook right now that I’m calling Fidelities: A Chronology. It has poems that wonder about the possibilities of our imaginations, whether we’re imagining Paleolithic times or the future, and to the things we stay faithful to. I’ll know if it’s working in a month or so. Then I’m taking some of the poems that have appeared in recent chapbooks and some that haven’t gone into those, and am beginning to think of a larger collection. The next full length book of poems. It is beginning to take shape in my mind. I also have the urge to do a novella and short story collection. The stories have appeared in various places, even in books, for the last 25 years or so. The novella needs to be finished and I’m not sure I can do it. I’ve been trying this summer. And lastly: what are you reading—or what have you read recently—that moved you? When I was thinking of that urgency in the question above, I was thinking of Tarfia Faizullah’s Seam. Wow, what a book! What a first book! I learn so much from that book, about a history I didn’t know, about making poems, about being a more complete person. And this is by a writer who is half my age. Read that book, Matt. I also just reviewed the new collection by John Repp, Fat Jersey Blues. It won the Akron prize last year and was just released. He is a poet of my generation who hasn’t had the attention he deserves. Intense oblique narratives about his blue collar family and his own engagement with literature. I’m spending time with the Selected Poems of Adonis, translated by Khaled Mattawa. It’s exhilarating to move into a kind of poetry that is so different from anything being done on this continent. Novels, collections of short stories, non-fiction, essays, popular science. I read it all. I continue to be curious enough to read it all, even if I doze off more. Two poems from The Ancient Murrelet:

When the Girls Arrived in Copenhagen and left the station, near midnight, snow fell in soft piles on their hats and backpacks. No cars or people passed while they walked down the hushed streets. Through windows without blinds or curtains they could see Danes bathed in blue television light or quietly reading in uncluttered rooms small novels perhaps about two girls long ago walking through snow. Chasing the Ancient Murrelet Ancient… because of a grey mantel thrown over its shoulders, which look hunched against the weather of the North Pacific, its real home, too far from this place at the edge of Lake Michigan to be imagined, where the untouched but beautiful young run down the beach in summertime longing to leave their parents who make steel appliances and claim to love the wind and winter. The bird is lost or brave or blown here by westerlies strong enough to reshape its instincts, to bring it down to the dirty mouth of a river that drains the abandoned car factories of South Bend, and the ancient murrelet bobs in these choppy irregular fresh water swells, diving, often, after crustaceans that haven’t lived here for a geologic epoch, but taking what minnows it can find to keep hunger off until it dies, here, in a place it doesn’t belong, where it can’t find the right food or mate, but where I find it, following clear directions on the internet, to catch a quick glimpse-- as it rises between waves-- of its two-toned bill, and the large head-- bulky, oversized on its small diminished body. Order The Ancient Murrelet from Alice Green & Co.

1 Comment

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed